In the third post of “The Evolution of Metacognition in Biological Sciences” guest series, Dr. Chris Basgier describes the workshops series led by Office of University Writing and the Biggio Center that helped the department redefine metacognition in such a way that they felt like they could understand it, teach it, and assess it. He also unpacks the value of the new definition and points to the work ahead as Biology embraces ePortfolios as part of a pedagogical strategy to increase metacognition in their students.

by Christopher Basgier, Associate Director of University Writing

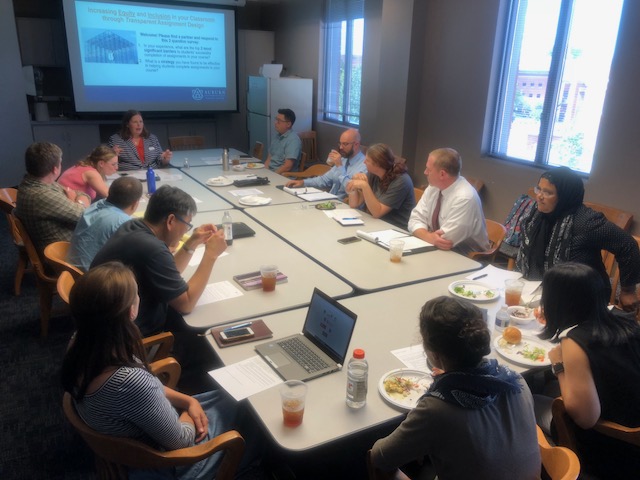

In the fall semester of 2018, Lindsay Doukopoulos and I had the opportunity to guide faculty from Auburn University’s Department of Biological Sciences (DBS) through a series of workshops devoted to metacognition. These workshops were a direct response to the “metacognition massacre” that had occurred at the August 2018 faculty retreat, as Dr. Robert Boyd recounted in the first blog post in this series.

Essentially, DBS faculty were uneasy with the definition of metacognition contained in the department’s student learning outcome (SLO), and unsure how to implement metacognitive activities in their courses. Working together, Lindsay and I decided to use these workshops to introduce faculty to the principles of transparent assignment design, offer guidance on integrating reflective writing into courses, and work with them to redefine the metacognition SLO in more familiar terms.

Transparent Design

We began with transparent assignment design and reflective writing—rather than the SLO—to generate faculty engagement in metacognition. With concrete such strategies for promoting metacognition under their belts, we decided, faculty would be more invested in redefining the SLO and more willing to commit to aligning their courses to that outcome.

Lindsay led the effort to introduce transparent assignment design to DBS workshop participants. According to Mary-Ann Winkelmes with TILT Higher Ed (2016), transparent assignment design invites faculty to clarify how and why students are learning course content in particular ways. Transparently designed assignments include

- The assignment’s purpose, including the skills they will practice and the knowledge they will gain

- The task, including what students will do and the steps they should take to complete the assignment

- Criteria for success, including a checklist or rubric and examples of successful student work

From our perspective, transparently designed assignments can promote metacognition. They make explicit what is often implicit in course assignments, and they help students see how a given assignment fits within the larger context of a course, and even a curriculum. The best designed assignments show students how to draw on what they already know, and help them imagine future implications of their work.

We gave faculty ample time during the first workshop to consider how they would revise one or more assignments using the transparent assignment design framework, but we also knew that students needed to take an active role in their learning if they were to enhance their metacognitive capabilities. Therefore, I led a second workshop on reflective writing.

Reflective Writing Component

In Auburn’s Office of University Writing, where I work as Associate Director, we spend a lot of time introducing principles of reflective writing to faculty, namely because we are in charge of the ePortfolio Project, which is Auburn’s Quality Enhancement Project required for accreditation in the SACSCOC.

The ePortfolios we support are polished, integrative, public-facing websites that students can use to showcase their knowledge, skills, and abilities for a range of audiences and purposes. A key component of ePortfolios, reflective writing is a metacognitive practice that invites students to articulate learning experiences, ask questions, draw connections, imagine future implications, and repackage knowledge for different audiences and purposes. After introducing DBS faculty to various levels of reflective writing, I gave them time to develop a reflective writing activity that would support a project or experience already in play in the courses.

Our hope in these first two workshops was to give DBS faculty practical tools for promoting metacognition in their courses that would not require wholesale course redesign. Transparent assignment design and low-stakes reflective writing are fairly easy to implement in most course contexts.

Redefining the Metacognition Learning Objective

Our third workshop required more intellectual heavy lifting, as it focused on redefining the metacognition SLO. The original metacognition SLO read as follows:

Students will develop metacognitive skills and be able to distinguish between broad categories of metacognition as applied to their major. In particular, they will distinguish between foundational (i.e., knowledge recall) and higher order (i.e., creative, analysis, synthesis) metacognitive skills.

The trouble with this definition is that it seems to require students to be able to define different kinds of metacognition (which is difficult enough for faculty), rather than put different kinds of metacognition into practice, regardless of whether or not they can name the metacognitive “categories” they are using.

As an alternative, I turned to research by Gwen Gorzelsky and colleagues, scholars in writing studies who developed a taxonomy of kinds of metacognition. In their framework, the richest form of metacognition is constructive metacognition, which they define as “Reflection across writing tasks and contexts, using writing and rhetorical concepts to explain choices and evaluations and to construct a writerly identity” (2016, p. 226).

Attracted to the notion that metacognition involves reflection on choices and the construction of identity, Lindsay and I tried our hand at a revised definition:

Metacognition is defined as the process by which students reflect on and communicate about their role in learning. Reflection and communication may include: 1. students’ choices made in response to the affordances and constraints on learning, and/or 2. students’ evaluations of the success of such choices, particularly across tasks and contexts. Ultimately, these activities should help students develop and articulate identities as scientists.

Our goal in composing this definition was not to suggest to DBS faculty that it was the right one, only that alternatives were possible. During the final workshop, we asked them to review the original SLO as well as our alternative, and then apply some “critical resistance” to each by reflecting on which terms or ideas made sense, which did not, and what language they might like to include. After much discussion, the group developed a revised SLO:

Students will develop their metacognitive skills. Metacognition is defined as the process by which students reflect on and communicate about their role in learning. Reflection and communication may include: 1. Awareness of choices made in response to the opportunities (i.e., homework, office hours, review sessions) and constraints (i.e., challenging problems, short time frames) on learning, and/or; 2. Evaluation of the success of such choices, particularly across tasks and contexts. Ultimately, these activities should help students develop and articulate their science knowledge and its value to their professional and lifelong learning goals.

This definition includes some key changes and additions. It eliminates jargon like “knowledge recall” and “affordances” in favor of more accessible language like “opportunities,” which are further defined in parentheses. Faculty also pushed back on the idea that all students should develop identities as scientists. A great number of students who take DBS courses plan to go into medical fields, so instead, they wanted to put the emphasis on science knowledge, a much more portable focus than science identity. They also added the notion of professional and lifelong learning goals to acknowledge the varied contexts in which their science knowledge might be relevant.

In the end, our metacognition workshop was a success: the department approved the new definition in December 2018, and many commented on how much clearer and easier to implement and assess it appeared. But our work is not done. Faculty still need to integrate metacognition throughout the curriculum—or at least in courses where it is feasible. The department has agreed that ePortfolios are an effective vehicle for doing so.

ePortfolios to Support Implementation

DBS had joined the ePortfolio Cohort (the group of departments and units committed to implementing ePortfolios) in 2017, and have been working steadily on implementation. Valerie Tisdale, the department’s academic advisor, began the effort to introduce ePortfolios in BIOL 2100, a professional practice course for undergraduate biology majors, in fall 2018. Most recently, in spring 2019, DBS faculty applied for and were awarded with a grant to support an intensive summer workshop to further the integration of ePortfolios in support of metacognition and written communication. My colleague Amy Cicchino and I met with three department members—Lamar Seibenhener, Joanna Diller, and Valerie Tisdale—for four weeks in summer 2019. Utilizing the resources of the ePortfolio Project, the departmental team developed a host of materials for a new, required course that asks students to complete their final ePortfolios during their senior year.

In the interest of transparent assignment design, they also created an ePortfolio “roadmap” that would help DBS majors understand what an ePortfolio is, why it is important for students in the sciences, and where in the curriculum they might encounter artifacts that could be used as evidence of their knowledge, skills, and abilities. The department approved the new course and completed the roadmap at a retreat in late 2019.

At this point, we are awaiting university-level approval of the new course. In the meantime, we are also planning workshops for DBS faculty on designing meaningful assignments that can be used as ePortfolio artifacts. Taken together, these efforts will help DBS support metacognition through ePortfolios in the years to come.

References

Gorzelsky, G., Driscoll, D. L., Paszek, J., Jones, E., & Hayes, C. (2016). Cultivating constructive metacognition: a new taxonomy for writing studies. Critical transitions: Writing and the question of transfer, 215.

Winkelmes, M. A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success. Peer Review, 18(1/2), 31-36.