by Gina Evers, M.F.A., Director of the Writing Center and First-Year Experience Coordinator

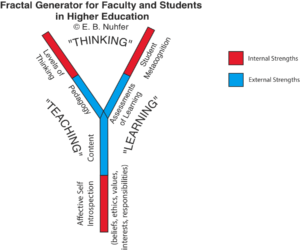

Metacognition as Recursion

One of my refrains as a writing teacher is “everything is connected, and it’s your job to figure out how.” Of course, the process of identifying connections between seemingly disparate ideas is a metacognitive one: writers must cultivate an awareness of how they think about a particular concept in order to think about it differently. And through this reconsideration, this intellectual quest to discover parallels, translations, or evolutions among ideas, new meanings are made and beautiful thesis statements are born!

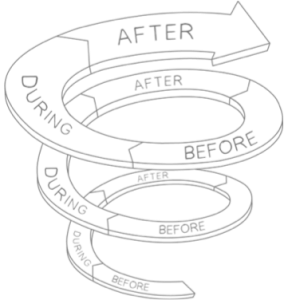

While the process of birthing knowledge from chaos may seem magical, composition scholars have articulated it in many articles defining the writing process as recursive rather than linear.  My favorite definition of recursion, because it is both practical and magical, comes from the work of Sondra Perl (1980/2008). In order to write recursively, Perl advises us to engage in three tasks. The first she terms “retrospective structuring,” or a looking back to what a writer has already written while reconciling it with their present thoughts and compositions (p. 145). Perl names the second task “projective structuring,” or a looking forward to predict the responses and questions of readers (p. 146). Again, writers use those anticipations to inform how they compose in the present. And here comes the magic: “felt sense,” a term (Perl attributes to philosopher Eugene Gendlin) and uses to describe a writer’s intuition about what feels right to them (p. 142). Perl argues that engaging in felt sense is crucial for both effective retrospective and projective structuring.

My favorite definition of recursion, because it is both practical and magical, comes from the work of Sondra Perl (1980/2008). In order to write recursively, Perl advises us to engage in three tasks. The first she terms “retrospective structuring,” or a looking back to what a writer has already written while reconciling it with their present thoughts and compositions (p. 145). Perl names the second task “projective structuring,” or a looking forward to predict the responses and questions of readers (p. 146). Again, writers use those anticipations to inform how they compose in the present. And here comes the magic: “felt sense,” a term (Perl attributes to philosopher Eugene Gendlin) and uses to describe a writer’s intuition about what feels right to them (p. 142). Perl argues that engaging in felt sense is crucial for both effective retrospective and projective structuring.

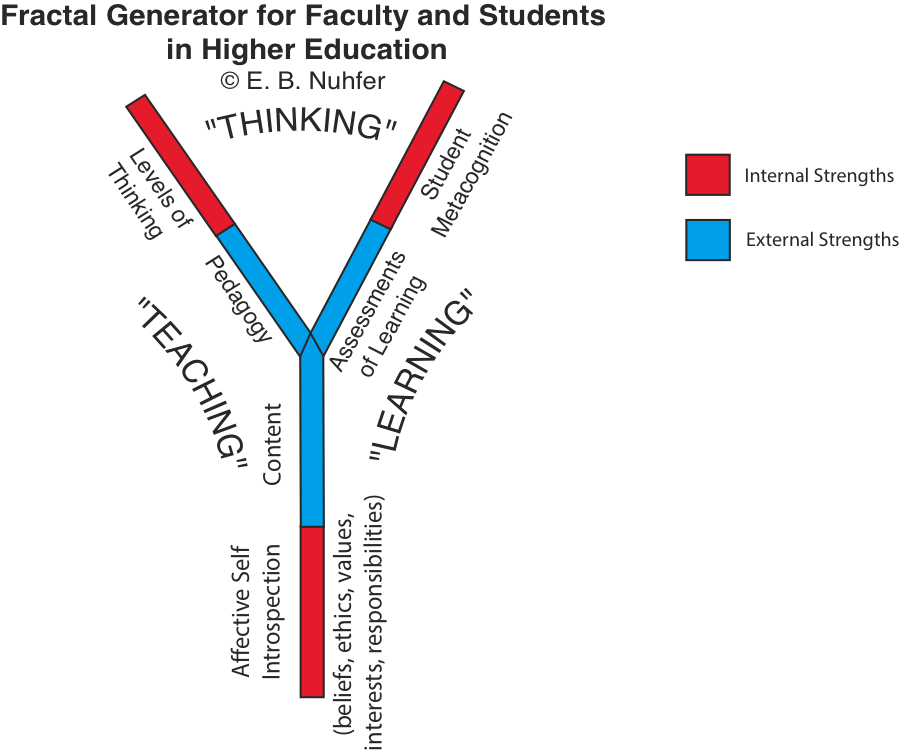

I argue metacognition is at the heart of felt sense; metacognition is the practical key needed to unlock the magic of that writerly intuition. And because that writerly intuition is crucial for recursive writing and thinking, engaging in metacognition is a recursive process while, likewise, writing recursively is inherently metacognitive. These theoretical connections became clear to me throughout my Writing Center work in the Spring 2022 semester, when I focused my tutor training program on anti-racist tutoring practices.

Connecting the Writing Center to DEI Work: A Beginning

To open our first staff meeting that focused on anti-racist tutoring, I asked my undergraduate writing tutors to compose and share a six-word memoir describing the first time they became aware of race. Here is mine:

- I wanted braids; Mom said no.

And here are two from my team:

- Middle school history class.

- No one else looked like me.

The first and third memoir show personal confrontations with difference, while the second shows a more removed interaction, where difference is explained in an academic setting. This diversity is relevant as we consider how we think about our roles as educators with a commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Each student brings with them distinct personal and academic histories of race and racism, and those histories take up space in our classrooms — even if we do not see or acknowledge them.

Examining this writing activity through the lens of a recursive metacognition / a metacognitive recursion, we see that in the present moment of the staff meeting, tutors were asked to look back to their earliest memories of learning race (retrospective structuring). For me as the educator, learning about the background knowledge of my students allowed me to look forward and tailor the forthcoming activities and lessons to the needs of my specific audience (projective structuring). The felt sense – what I argue is actually recursive metacognition / metacognitive recursion – then emerged through our sharing and discussion. In conversation, we reconciled those early learnings of race with what we know now.

Seeing the Metacognitive Recursion in my Own Process

The six-word memoir activity came from “Talking Justice: The Role of Antiracism in the Writing Center” (2019) – a piece of scholarship authored by peer writing consultants at Oklahoma State University. In it, the authors describe the six-word memoir as a part of the anti-racist training they created for writing center staff at OSU. The authors articulate three goals of their training:

- Cultivate a “willingness to be disturbed,” to disrupt our own individual ways of thinking and being that have continued systemic racism, which demands “a tireless investment in reflection, openness, and hope for a better, more fulfilling future for us all” (Diab et al. 20).

- Create (brave) spaces where people are able to discuss issues and concerns surrounding race and racism with a willingness to be wrong, to call out with compassion, and to seek mutual understanding.

- Enact mindful inclusion practices that support diverse writers and resist the writing center’s historical role in gatekeeping and assimilating for academic institutions. (Coenen et al., 2019, p. 14)

Looking Back

These goals – then and now – strike me as particularly metacognitive. The intentional awareness that engaging in anti-racist training will cause disturbance demonstrates a tutor’s willingness to take risks in their thinking and learning. Similarly, creating space for conversation within this plane of disturbance and “mindfully … resist[ing] the writing center’s historical role [of] assimilating” students into the academy both demonstrate contemplation about the ways of knowing we have all participated in.

Looking Forward

In order to honor Coenen et al’s goals in my own tutor training, I concluded my first staff meeting that focused on anti-racist tutoring by asking tutors to anonymously contribute to a staff Padlet. On it, they described ways a writing center – any writing center – could participate in, support, or condone racism. After doing this work, my tutors then contributed to a working document that listed ways our Mount Saint Mary College Writing Center could combat racism and resist complicity with racism.

Recursive Metacognition and Anti-racist Tutor Training

But what of Perl’s magical ingredient? Where does felt sense – recursive metacognition – appear in my facilitation of this first anti-racist tutor training? I knew my tutors needed a structure, so I adapted the six-word memoir activity. I knew my tutors needed to feel empowered with agency to create change, so I chose an article authored by their contemporaries: other peer tutors. I knew my tutors needed to understand how a writing center could contribute to institutional racism without blaming or shaming their tutoring practices, so I created an anonymous Padlet as a forum for this conversation. I knew my tutors needed to be included in creating solutions to correcting racial injustice on campus, so I allowed them to generate a list of action steps we could take as a Writing Center and helped us achieve them.

This knowing I am describing is more than an intuition, a “felt sense”: it is metacognitive awareness I have cultivated as an educator. And put into recursive practice, metacognition becomes a mighty pedagogical tool that can unlock thinking and writing processes for students and educators alike.

References

Coenen, H., Folarin, F., Tinsley, N., & Wright, L. (2019). Talking justice: The role of antiracism in the writing center. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 16(2), 12-19.

Perl, S. (2008). Understanding composing. In T. R. Johnson (Ed.), Teaching Composition: Background Readings (pp.140-148). Bedford/St. Martin’s. (Reprinted from “Understanding composing,” 1980, College Composition and Communication, 31[4], 363-369, https://doi.org/10.2307/356586).