By Yianna Vovides, PhD and Marie Selvanadin, MS, MBA, Georgetown University

We see the process of design and development of products as very much a metacognitive awareness process given that designers and developers are engaged in cycles of reflection, planning, monitoring, and evaluation with every prototype produced. This is especially the case when embarking on the development of a virtual learning environment (VLE) because of the fact that the environment itself needs to enable and support engagement toward varied types of learning and meet the needs of both instructors and students. In this blog post we discuss the design and development process of a VLE, a web-based case analysis app developed by the Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship at Georgetown University. We highlight how the metacognitive design process of planning, monitoring, and evaluation supports a reflective practice that enables metacognitive learning.

Context: Ethical Decision Making for Global Managers (GUX)

The case analysis app was designed to augment case-based teaching and learning techniques by providing multiple ways for students to reflect on their thinking in relation to how they make decisions. In collaboration with a faculty member and program director, we approached the design of the app by contextualizing it within the Ethical Decision Making for Global Managers professional certificate offered via edx. The main goal that the app was designed to support learners in achieving is the following: “how to analyze real-world ethical dilemmas using multiple frameworks, considering many possible choices, and selecting a “best choice” option.” The courses in the certificate program focused on rules- and results-based decision-making processes.

Teaching decision-making, let alone ethical decision-making, is not easily done and doing so online, especially within an open self-paced learning environment, is even more challenging (Sternberg, n. d.).

Sternberg emphasizes that:

“[l]earning how to reason ethically is a dialectical, back-and-forth process. Simply delivering content through lectures and readings are at best supplementary forms of instruction. The primary form of instruction needs to be interactive because students need to present ideas, get feedback on those ideas, and then try out re-formed ideas that themselves will be subject to further modification.”

With this in mind, we knew that we needed to design the app in a way that enabled individuals to engage in a back-and-forth process that could support ethical reasoning. We realized early on that in order to make the interaction within the case analysis app meaningful to individual learners, the app itself needed to provide guidance at both the cognitive and metacognitive levels. Therefore, we needed to consider how the app itself could “speak” to the learner. In other words, what interaction could we design as part of the app to provide feedback to the learners along the way so help them reflect about their decision-making process and how they were using the rules-based and results based ethical reasoning approaches.

Our collaboration with the faculty and program director in relation to this project took place over two years, so we had time to understand and internalize the ethical decision-making framework that was being used in the courses which focused on rules-oriented and results-oriented approaches. For enabling both cognitive and metacognitive interactions within the app, we used the reflective sensemaking model (Vovides and Inman, 2016) to guide our design decisions. Sensemaking as a pedagogical approach to teach ethics has been gaining attention (Brandt and Popejoy, 2020).

The following section breaks down the design of the app in relation to the reflective sensemaking process. It includes screenshots taken from the web-based app itself using a case study being used in the Ethical Decision-Making for Global Managers professional certificate available on edx.

Design: Reflective Sensemaking

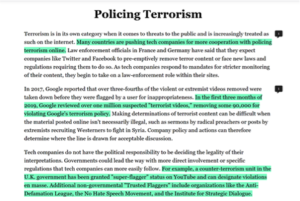

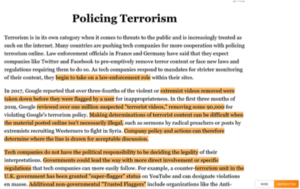

- The reflective sensemaking process begins by asking a learner to explore a real-world case. The example we show in the screenshots is related to Policing Terrorism.

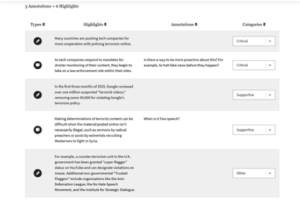

The learner is encouraged to read the case multiple times. A learner has the option to highlight and/or annotate parts of the case and to determine whether they want their annotations to remain private (visible only to them) or made public (visible to others interacting with the same case).

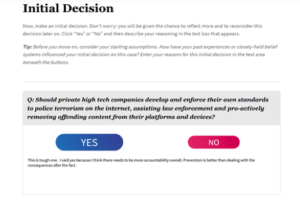

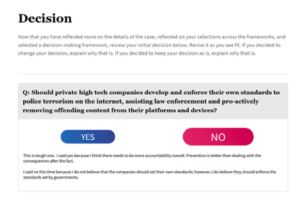

- The learner is then asked a yes/no question about the key issue described in the case study In the Policing Terrorism case study, they are asked whether private high tech companies should develop and enforce their own standards to police terrorism on the internet.

Once the learner selects either yes or no, they are asked to write down the reasoning for their decision.

After this initial decision, the learner is presented with their own highlights and annotations from their reading of the case and asked to identify how important each highlight and annotation was in contributing to their decision.

After this initial decision, the learner is presented with their own highlights and annotations from their reading of the case and asked to identify how important each highlight and annotation was in contributing to their decision.

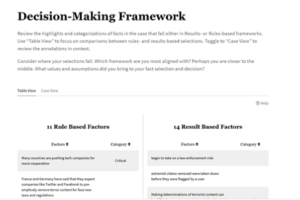

4.  Then, the learner is shown a summary of where their highlights/annotations fall within the Rules and Results decision-making framework. They are asked to consider the following questions:

Then, the learner is shown a summary of where their highlights/annotations fall within the Rules and Results decision-making framework. They are asked to consider the following questions:

-

- Which framework are you most aligned with? Perhaps you are closer to the middle.

- What values and assumptions did you bring to your fact selection and decision?

In addition, the app provides learners the option to see their highlights and annotations in context and explore how the instructor engaged with the same case. This aims to reduce the feeling of anonymity and isolation. We also see it as a way to enable further exploration of the case itself.

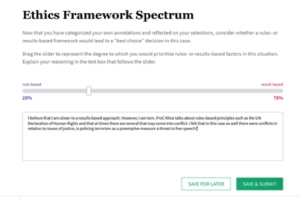

The learner is then asked to consider whether a rules- or results-based framework would lead to a “best choice” decision in the case they read. They are asked to use a slider to represent the degree to which they would prioritize rules- or results-based factors and then to explain their reasoning.

The learner is then asked to consider whether a rules- or results-based framework would lead to a “best choice” decision in the case they read. They are asked to use a slider to represent the degree to which they would prioritize rules- or results-based factors and then to explain their reasoning.

By allowing students to take the time to reflect on their learning and decision making, we believe that they are given the opportunity to think about their own thinking (which in simplistic terms is what metacognition is all about) and giving them an opportunity to reflect on their learning.

By allowing students to take the time to reflect on their learning and decision making, we believe that they are given the opportunity to think about their own thinking (which in simplistic terms is what metacognition is all about) and giving them an opportunity to reflect on their learning.

As a final step in the reflective sensemaking process, learners are asked the same yes/no question and given another opportunity to either keep the same decision or change it. In either case, they are asked to explain their reasoning. The focus in this particular example is related to ethical reasoning; however, the approach could be used for other types of reasoning.

As a final step in the reflective sensemaking process, learners are asked the same yes/no question and given another opportunity to either keep the same decision or change it. In either case, they are asked to explain their reasoning. The focus in this particular example is related to ethical reasoning; however, the approach could be used for other types of reasoning.

Model: Where Learning Design and Analytics Align

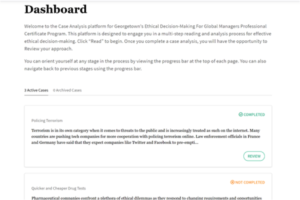

This case analysis app presents one model for how learning design and analytics can come together to create a unique experience where reflection of the learning process is prioritized. Reflection is critical in developing metacognitive awareness (Schraw, 1998). We designed the app so that learners can go through multiple cases as they move through the Ethical Decision Making for Global Managers professional certificate program. Once learners complete one case then they continue to have access to it for review purposes in the app’s dashboard (shown here). Encouraging review of one’s completed cases enables learners to become more aware of how they reasoned through that case.

This case analysis app presents one model for how learning design and analytics can come together to create a unique experience where reflection of the learning process is prioritized. Reflection is critical in developing metacognitive awareness (Schraw, 1998). We designed the app so that learners can go through multiple cases as they move through the Ethical Decision Making for Global Managers professional certificate program. Once learners complete one case then they continue to have access to it for review purposes in the app’s dashboard (shown here). Encouraging review of one’s completed cases enables learners to become more aware of how they reasoned through that case.

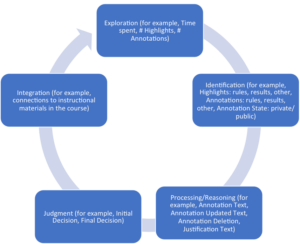

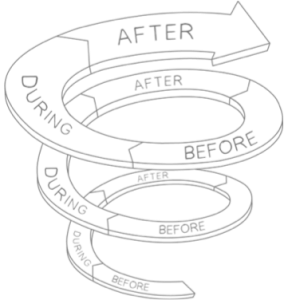

To align the learning design and analytics we began with a conceptual data model which we are still refining (see Sensemaking Process with Identified Variables diagram). We took the reflective sensemaking process and have started mapping the variables that could serve as proxies to better understand how learners are making sense of the case they are engaging with. We considered the number of different actions that a learner takes when reading the case itself. We also take into account whether the learner goes back and reviews the case, and more. This type of mapping of the data to the learning process will enable us to make the learner journey visible to the learner because we will be able to create a visualization of the reflective sensemaking process as they engage with the cases.

Therefore, our next step is to create the visualization of the sensemaking process for each learner who goes through a case that will be available as part of the learner dashboard in the case analysis app. Given that a learner could go through multiple cases, the visualization would also represent the learner’s sensemaking process across cases and over time. We envision that the dashboard itself could then become an active learning space that would support further metacognitive awareness as it would enable learners to interrogate how they reasoned through multiple cases over time.

Our Reflection so Far in relation to using metacognitive design to support metacognitive learning

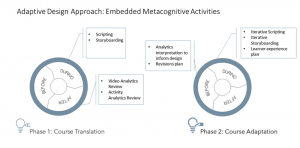

To design a learner dashboard as an active learning space requires an adaptive learning design process so that we can account for changes from one iteration to the next as we gain a better understanding of how learners are engaging with the app. Given that adaptive learning design is a process that strategically modifies designs based on emerging learner needs (Bower, 2016), we incorporated from the start of this project reflective pauses to become even more aware of our own iterative approach. We planned what we would do before we developed a prototype, during our prototyping process, and after when conducting formative evaluations. Yes, it has taken two years so far!

The app launched in 2020 and we are currently in the process of collecting learner data from the platform and surveys to help us solidify some of the functionality that would be part of the active learning dashboard. We are also investigating options to introduce social learning opportunities as part of the active learning dashboard to reduce the sense of isolation and anonymity. Want to learn more, contact us!

References

Bower, M. (2016). A Framework for Adaptive Learning Design in a Web-Conferencing Environment. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, (1).

Brandt, L., & Popejoy, L. (2020). Use of sensemaking as a pedagogical approach to teach clinical ethics: an integrative review. International Journal of Ethics Education, 1-15.

Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional science, 26(1-2), 113-125.

Sternberg, R. J. (n.d.). Developing ethical reasoning and/or ethical decision making | IDEA. IDEA. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.ideaedu.org/idea-notes-on-learning/developing-ethical-reasoning-and-or-ethical-decision-making/

Vovides, Y., & Inman, S. (2016). Elusive learning—using learning analytics to support reflective sensemaking of ill-structured ethical problems: A learner-managed dashboard solution. Future Internet, 8(2), 26.