By Zhuqing Ding, MA

What’s the interaction like in higher education between faculty and instructional designers? While faculty often have full autonomy in their course design and teaching methodologies (Martin, 2009), instructional designers play the role of a change agent. When instructional designers propose improvements in instructional strategies and recommend significant changes to existing courses, faculty may resist adopting their recommendations. With this in mind, the online course design team at the Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship (CNDLS), Georgetown University, had implemented an adaptive approach to the course design process since 2018. During the pandemic, we were able to pivot and expand this approach to offer support to faculty across the university and not only to the ones who had been part of online programs.

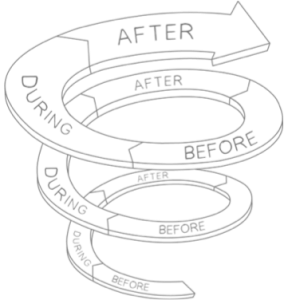

So, what makes our process adaptive? The traditional ADDIE (Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement and Evaluate) instructional design model, focuses on linear processes in content development. Compared to the traditional instructional design approach, an adaptive approach has distinct iterative phases where we use learning analytics as evidence to initiate faculty members’ metacognition, thereby inspiring changes to future iterations of the course.

Here is how our course design team implemented the adaptive approach for transforming an existing classroom-based law course to fully online. Before moving online, this tax law course was offered once a week through one 2.5-hour lecture, accompanied by reading assignments and graded only by one final exam. During the first phase of our adaptive process our team tackled the following questions:

- How can we transform the passive learning experiences in the classroom (receiving information) into active learning (interacting with the course materials)?

- How can we strike a balance between good practices for online course design and the traditional methods familiar to/preferred by law school professors?

- What are some of the strategies we will use to encourage the faculty members to evaluate their own teaching strategies to become more mindful and intentional about their own teaching?

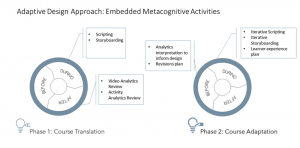

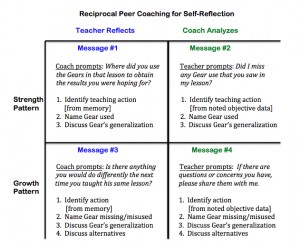

While lecturing has been proven to be the most used instructional method, especially in higher education, it is more suitable for a face-to-face traditional classroom than an online environment (McKeachie, 1990). In an online course, passively receiving a large amount of information by watching a series of 2.5-hour lectures can be challenging for students. Following an adaptive process allowed us to guide faculty toward an awareness that designing an online course is more than recording lectures and that students need to interact with the lectures in order to be able to recall and retrieve what they are learning. The following image shows the metacognitive activities that we incorporated in the adaptive design approach. During the first phase of the course, our course design team introduced activities that support reflective practice to enable faculty members to become more self-aware about their own teaching and learning. Then, in the second phase we introduce activities that encourage a deepening of the reflective practice to spark creativity.

Interactive and short lectures

In order to collect data that can help us understand the students’ learning experience, we proposed to the faculty to create interactive and short lectures to replace the 2.5-hour long lectures in each module. To demonstrate to faculty the types of interactive elements that can be inserted into lectures, we introduced a storyboarding method. In the script, the faculty broke their long lectures into subtopics. Our instructional designers highlighted the keywords and areas that could be illustrated by graphics or animations. Then, the faculty confirmed the highlights and the graphics, and added/deleted as needed.

The resultant, short, subtopic videos were presented as playlists in the course. Within each video, the professor is shown lecturing on the right side of the screen, and on the left, relevant animated keywords, charts, and graphics appear. Certain parts of the charts were highlighted as the professor talked through certain elements within the charts. Such interactive elements within the lectures are designed to help students make a connection to the professor while also focusing on important keywords and short summaries of the lecture topics.

The analytics report provided by the video hosting platform that became available after the course launched helped with the faculty’s meta-thinking. Based on the total views, total minutes of content delivered, unique viewers, and the percentage of completion data for each video, the course team was able to understand important aspects of the students’ learning experience: the videos that had the highest views, the videos that students were not able to finish watching, and the videos that students watched again and again. Such evidence helped the faculty identify knowledge areas that students were not able to understand right away and recognize times when students’ participation dropped.

In the second iteration/phase of this course, the faculty took several actions to not only improve the course design, but also improved his teaching presence in this online course. First, during the low-participation time observed from the analytics report of the first iteration, reminders were sent to students to encourage them to keep up the pace. Additionally, more office hours including one-on-one and group office hours were scheduled, allowing students to clear up questions with the professor if they got stuck. The faculty was able to address common questions during the recorded office hour sessions, and made these sessions available to students. Overall, the student-faculty interaction was improved since, due to metacognition, the faculty became more aware of the importance of building interactive touch points to keep online students on track. The metacognition has initiated his awareness of the importance of the teaching presence in the online courses.

Weekly Activities

The law school has a long-standing tradition of using final exams as the only assessment in a given course. In face-to-face classes, interactions such as small talk among peers before and after the class and question-and-answer sessions after each lecture help students confirm whether they are on track. For online students, such checkpoints are missing and, therefore, it is necessary to periodically build them in so students can make sure they are following along.

In the first iteration of the course, we introduced weekly, ungraded quizzes, allowing students to practice, experiment, and reflect on their learning. Since this particular course is related to tax law, the quiz questions — most requiring calculation in Excel — were extracted from previous exams. Correct answers and short explanations were provided for each question at the end of the quiz. Students were allowed to take the quizzes multiple times. Such low-stakes activities provided the space for students to explore and discover the answers during their learning.

After the first iteration of the course, the professor was able to review the quiz analytics report provided by the quiz tool in Canvas, which allowed for metacognition on the activity design. There was a correlation between students’ performance on the weekly quizzes and the final exam. Students who didn’t participate in the practice quizzes at all achieved lower scores than students who did. Students who completed practice quizzes were also more active in the online office hours and found more opportunities to engage with the professor throughout the semester. Based on this finding, the professor realized the importance of motivating students to practice on a weekly basis in order to assess their understanding and ask questions before they fall too far behind.

By the second iteration of the course, a few actions were taken to improve students’ engagement in weekly quizzes. The professor improved the design of the quiz questions by adding downloadable Excel spreadsheets with formulas to the provided explanations of the quiz answers, allowing students to tinker with formulas and reflect on their own calculations. He also offered additional office hours following the quizzes in each module to make sure students had the opportunity to ask questions.

The professor moved from reluctance to including weekly quizzes at all, since they didn’t exist in the face-to-face class, to encouraging active learning processes by improving the quiz question design and proactively providing space for students to reach out to him with questions. Quiz analytics served as evidence that drove the faculty member to metacognition and improved the way he teaches online.

Summary

Metacognition is implicitly part of faculty development programs across disciplines. However, while working with law faculty, the adaptive approaches our course design team followed led to new reflections about their teaching practice. It was challenging to find the balance between traditional ways of teaching in the law school and an interactive online course that would allow students to succeed in a virtual environment. The adaptive approach allows the instructional designers and faculty to reach more agreements with iterative efforts. We used the analytics provided by the media-hosting tool and the quiz tools as evidence to encourage meta-thinking about the faculty’s teaching practice. This led to minor changes to the course with significant impacts. With such evidence, faculty are more open to adapting their long-standing teaching practices and embracing new ways of designing online courses. Sometimes these metacognitive approaches to teaching online also inspire faculty to rethink their teaching practices in traditional classrooms, such as providing more measurable learning goals or diversifying assessment methods.

References

McKeachie, W. J. (1990) Research on College Teaching: The Historical Background, Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 2, 189-200.

Martin, R. E. (2009). The revenue-to-cost spiral in higher education. Raleigh, NC: John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED535460.pdf