Spring 2022: We asked folks, “What is your favorite metacognition “ah ha” moment that a student shared with you or you’ve experienced in the classroom?” Here are the responses:

- Randy Laist, “Stray Cats and Invisible Prejudices: A Metacognition Short-Take”

- Tara Beziat, “Is the driver really that far away?”

- Jennifer McCabe, “The Envelope, Please”

- Ritamarie Hensley, “Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages”

- Antonio Gutierrez de Blume, “Culture influences metacognitive phenomena”

- Kathleen Murray, “Metacognitive Thinking: A Mechanism for Change”

- Lindsay Byer, “Metacognition: Bringing Our Different Skills to the DEI Table”

- Gina R. Evers, “Vulnerability as a Connector”

- Ludmila Smirnova, “The Power of “Ah-ha Moments” in Collaboration”

- Marie-Therese C. Sulit, “Metacognition with Faith, Trust, and Joy in the Collaborative Process”

- Sonya Abbye Taylor, “What the World Needs Now: The Power of Collaboration”

Stray Cats and Invisible Prejudices: A Metacognition Short-Take

by Randy Laist, University of Bridgeport

We had reached the point in our freshman writing class where the students described the topics they were choosing for their research papers. Samara had a brilliant idea to conduct research inspired by the stray cats she had seen on campus. After praising the originality and perceptiveness that led her to propose this line of inquiry, I casually editorialized regarding what I thought everyone knew about stray cats: that they were “super-predators” that menaced birds and squirrels, laying waste to backyard ecologies. The other students followed my comments with their own observations and questions about stray cats, but I noticed that Samara seemed somehow crestfallen and remote.

The following week, we discussed the progress we had been making with our research, and, when it was Samara’s turn, she presented a catalog of evidence demonstrating that the stereotype of cats as super-predators is in fact completely erroneous. Stray cats, she explained, rarely eat birds and actually play an important role in controlling rodent populations, especially in cities. I couldn’t help but feel that she was directing this argument at me personally.

The perspective Samara supported through her research completely revolutionized what I thought I knew about stay cats, but, more fundamentally, her research confronted me with the invisibility of my own prejudices. So much of our lives and our thoughts consist of background “truths” that we acquire somehow at some point and that become an inert part of our mental architecture. They remain unquestioned, and they exert a constant influence on our thoughts and our behavior in ways that we rarely recognize. Samara’s independent thinking – the product of both her humanitarian principles and her academic inquiry – made me realize that I had been willing to believe terrible things about cats, even though I am myself a loving cat-owner. The experience made me feel more compassionate toward stray cats, more warry of my own perceived truths, and more appreciative of the role that academic research, observation-based inquiry, and interpersonal dialogue can play in challenging human beings to reprogram themselves for greater humility and empathy.

Is the driver really that far away?

by Tara Beziat, Auburn University at Montgomery

I had two female students who were great friends and happen to be in same class. One day when they were driving home from class, one pondered aloud if a sign on a truck was correct. It noted something about how the driver was x amount of feet away. As the two of them drove, they contemplated if the information on the truck was accurate. Something just didn’t seem right. They started to calculate the length of the truck. What they realized was they were using concepts we had learned in class that day to figure this “problem” out. They realized they were using critical thinking skills because they were objectively evaluating the information presented. But then as they realized what they were doing, they were also being metacognitive as thought about their thinking, as they drove down the road.

The Envelope, Please

by Jennifer McCabe, Goucher College

In my Human Learning and Memory course, my favorite metacognition “ah ha” moment comes during the final class period, when I return the sealed envelopes containing students’ first-day-of-class memories. On the first day, they record details about everything they have done in the past 24 hours, then mark routine (R) or novel (N) next to each event. They seal the written memories in an envelope, on which they write their names, and submit. (I promise to not open them.) During the final class, they try to remember as much as they can about that first day. Once they get started writing, I brandish the envelopes, at which point there are more than a few reactions along the lines of, “I totally forgot we did that!” and “I have no idea what I wrote!” As they are distributed, I suggest that just seeing the envelope can be an effective retrieval cue. Finally, the big metacognitive moment – opening the envelopes to discover what they wrote that first day! The reactions at this point are mostly along the lines of disbelief that they wrote so much more than they can remember now. This leads to a discussion of transience, and how they now have very personal evidence of how much we forget about our own lives. We also discuss episodic versus semantic elements of their memories, and whether routine or novel elements tended to be remembered best. I conclude with anti-transience strategies, such as keeping a journal or using social media to document life events.

Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages

by Ritamarie Hensley, Simmons University

After teaching at the high school level for many years, I knew students didn’t read the directions, finish assignments on time, or know how to write a coherent paragraph. Of course, these characteristics didn’t describe all of my students, but I often encountered these issues from year-to-year. So when I began teaching doctoral students for the first time, I assumed I would not need to worry about them turning-in late papers, writing illogical paragraphs, or ignoring my instructions.

Hence the aha moment.

Students are students and no matter what their age or level of education, they need me. They need me to teach the basics of writing a coherent paragraph. They need me to remind them when a paper is due. And, they need me to point out the directions… again. But, that’s okay. It’s what I do. Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages. Whether it’s earning a high school diploma or a terminal degree, people are busy and human, so they need their instructors to help them attain their goals, even if that means reminding them of the directions one more time.

Culture influences metacognitive phenomena

by Antonio Gutierrez de Blume, Georgia Southern University

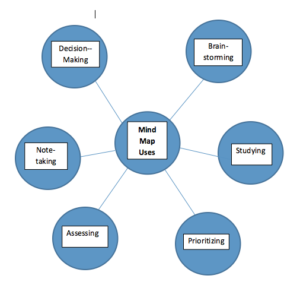

What is “metacognition”? What does it mean to experience or become aware of one’s own thoughts? Since John Flavell coined the term in 1979, metacognition has been colloquially understood as thinking about one’s own thinking or taking one’s own thoughts as the object of cognition. However, this definition is far from complete because, among other things, it assumes, without actual evidence, that metacognition is a universal construct that is consistently experienced by all people. Nevertheless, I began to think more deeply on this matter and decided it was time to empirically examine the homogeneity or heterogeneity of metacognition across cultures and languages of the world rather than make wholesale assumptions.

In a recent study with 366 individuals across four countries (China, Colombia, Spain, US) and three languages (Chinese, English, Spanish), a group of colleagues and I investigated the influence of culture on metacognitive awareness (subjective) and objective metacognitive monitoring accuracy. We discovered, much to our surprise, that metacognition is not a homogenous concept or experience. In other words, metacognitive phenomena are understood and experienced differently as a function of the cultural norms and expectations in which one is reared. Imagine that! Future qualitative research will hopefully help us understand why and how culture influences metacognitive phenomena, including among indigenous populations of the world.

If you had asked me 5 years ago where my research on metacognition would take me, I would have never believed it would be down this path. However, I am excited about the prospect of continuing down the path of intercultural/multicultural investigation of metacognition!

Metacognitive Thinking: A Mechanism for Change

by Kathleen Murray, Mount Saint Mary College

Pushing us to reflect and evaluate our own personal strengths and limitations, Chick defines metacognition as “the processes used to plan, monitor, and assess one’s understanding and performance” (2013). Metacognition allows us to recognize the limitations of our knowledge and encourages us to figure out how to expand our ways of thinking and extend our abilities. There is no better example of this principle in action than Mount Saint Mary College’s DEI Dream Team: a group of individuals from all different walks-of-life united in our common desire to expand our perspective and make a difference in the community. Inspired by Tell Me Who You Are, our Dream Team created a series of workshops designed to promote reflection and educate both faculty and staff on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Our moniker, “Dream Team,” was, in fact, coined after an “ah-ha” moment when I first recognized the unique nature of this collaboration. These team members pushed me to expand my way of thinking and facilitated my growth as both an individual and a future educator. As I sit here and reflect on the success of these workshops, I am overwhelmed by the power of metacognitive thinking and inspired by the difference that our group could make in the campus community. After experiencing this wonderful collaboration rooted in parity, I now understand that metacognition is more than a pedagogical process or professional concept. It is a powerful tool that can be used to inspire activism and change the world.

Reference:

Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved January 22, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/metacognition/.

Metacognition: Bringing Our Different Skills to the DEI Table

by Lindsay Byer, Mount Saint Mary College

I remember being in one of our virtual planning meetings when my “Ah-ha” moment clicked. I was surrounded by women who were, and still are, inspiring in their own right. There are six of us: two undergraduate students, including myself, two Education professors, one professor from Arts and Letters, and the Director of the Writing Center. Each of us brought different skills to the metaphorical table along with different perspectives on how to best achieve our goal of spreading awareness of diversity, equity, and inclusion on our campus. I was nervous, to say the least, but I quickly realized I was being heard! My opinions carried the same weight as everyone else in that meeting. This was an atypical experience for me in working with faculty.

Met with collective positivity, I kicked off the forum series with a workshop focusing on the individual’s identity. Knowing the importance of creating a safe space for all participants, I used vignettes from Tell Me Who You Are to introduce terms, like intersectionality, and I closed with the opportunity to create “I am” poems. At some point during our planning process, and after Katie coined it, we referred to ourselves as the Dream Team, which couldn’t have suited us more. We were able to collaborate with respect towards one another, support one another, and allow one another to lead. I learned so much from working with these women and I am proud to say I am a member of the Dream Team.

Vulnerability as a Connector

by Gina R. Evers, Mount Saint Mary College

I have worked in academia my whole career, and I am cognizant of the invisible lines of power that have traditionally defined relationships among students, professors, and administrators. In our collaboration, however, we were able to create genuine, equal relationships across these boundaries. And it seemed to happen without intentional effort. How? What allowed this “committee” to disregard our institutionally prescribed guardrails with ease?

When facilitating “Writing Through a Racial Reckoning,” I included a read aloud of Ibram X. Kendi’s Antiracist Baby. Dr. Kendi encourages us to “confess” after realizing we may have done something racist. I remember the burn of shame I felt the first time I encountered this methodology. But as an educator, I knew that if I was experiencing such a strong reaction, it’s likely some of my students were as too. I shared and acknowledged that talking about mistakes and questions moves us forward while silence upholds racist structures. Through making myself vulnerable, I was able to create a brave space for workshop participants and invite folks to share on genuine and equal terms.

The fact that our “committee,” comprised of people occupying different institutional roles with inherently varying power structures, was able to achieve parity in our collaboration was enabled by our union in DEI work. Discussions of our common text — sharing our vulnerabilities around the content and genuinely grappling with matters of identity — connected us as equal members of a team, poised to rise together.

The Power of “Ah-ha Moments” in Collaboration

by Ludmila Smirnova, Mount Saint Mary College

One of the most memorable experiences and pedagogical discoveries of the last year was the work of our Dream Team on a college-wide initiative around issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The first “ah-ha moment” was when a spontaneous group of diverse but like-minded people gathered together to collaborate on the design and implementation of the project. It was amazing to interact with teacher candidates and faculty from other divisions and offices outside of the traditional college classroom. What united us was our devotion to the importance of DEI on campus and the desire to bring this project to its success. The college chose an excellent book, Tell Me Who You Are, for a common read and the team voluntarily met to discuss and implement a series of workshops to engage college students and faculty in activities that centered the content of the book. That’s the power of metacognition—being aware of how to plan events, choosing strategies for implementing the ideas, and reflecting on them collectively. Our students experienced the “ah-ha moments” a number of times throughout this project. How captivating to observe how mesmerized our students were to communicate with their faculty and how grateful they were to see that their voices counted and that they were able to contribute their ideas to the project as equal partners! But the most astonishing outcome of this project was our team collaboration on the book chapter that allowed us to reflect on this experience in a series of personal vignettes.

Metacognition with Faith, Trust, and Joy in the Collaborative Process

by Marie-Therese C. Sulit, Mount Saint Mary College

As I choose a favorite metacognition moment, two simultaneous experiences capture that sense of “ah-ha!” for me: when we first came together as a planning team and when we met for our penultimate writing workshop for our book chapter. In Tell Me Who You Are, I found the plethora of vignettes so well rendered with storytelling so ripe and rich to address our DEI initiative that I envisioned a series of “Talk Story” and “Talk Pedagogy” workshops. Our Dream Team came together in answering this call that created and delivered a forum series for our campus. While not easy, it certainly seemed so as we almost intuitively balanced and counter-balanced one another through every step of this process: preparation, execution, reflection. This collaboration then brought a book chapter to life, requiring a series of writing workshops every Friday afternoon throughout the fall semester. In contradistinction to the forum series, the nature of and expectations for publication moved us in different directions with a deadline after the Thanksgiving holiday. All of us, in our respective roles, were likewise closing our semesters. So important to us, this commitment stretched us in ways that we had not been stretched: it was all in the timing. However, with this all-female cast, the mutual reciprocity of our collaboration–the teaching/learning, problem-solving and shared decision-making–remained the same but especially worked through our commitment to metacognition. In so doing, we also affirmed our sense of faith, trust, and joy in the process and with one another.

What the World Needs Now: The Power of Collaboration

by Sonya Abbye Taylor, Mount Saint Mary College

I saw pride in my students’ expressions when they completed a beautifully executed collaborative course project. They agreed each contributed to the success of the project: they were joyful! Brought back to a moment, the semester before, I felt that same joy and awe at an Open Mic session, the culminating event of a collaborative venture, I worked on with students and faculty. We created a series of workshops addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion. While the workshops were excellent, it was the collaborative process that impacted me as being the most meaningful, just as it was for those students. Wide in age-range, from different ethnicities, different backgrounds and frames of reference, our diverse group—two undergraduates, two Education faculty, one Arts and Letters faculty member, and the Director of the Writing Center—functioned as true collaborators. We had parity, as everyone’s ideas weighed equally, we listened actively and empathetically to one another, and we communicated effectively. Committed to a common goal, and having achieved it beyond our expectations, I knew at that “ah ha” moment something very special had happened. I knew, without having been taught the aforementioned skills essential for effective collaboration, we had been successful. I realized the power of collaboration and bemoaned the lack of opportunities to practice collaboration in schools. When we teach collaboration, we teach skills for life. I learn and contribute when I collaborate; I want my students do the same. People, willing and able to collaborate, can change the world.

*Reference:

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education. (2011). Just Write! Guide. Washington, DC