Welcome to Improve with Metacognition!

Metacognition is the use of reflective awareness to make timely adjustments (self-regulation) to behaviors that support a goal-directed process (e.g. learning, teaching, driving, cooking, writing).

Through metacognition, one should become better able to accurately judge one’s progress, and select and engage in strategies that will lead to success.

Author: Lauren Scharff

Fostering Metacognition to Support Student Learning and Performance

This article by Julie Dangremond Stanton, Amanda J. Sebesta and John Dunlosky “outline the reasons metacognition is critical for learning and summarize relevant research … in … three main areas in which faculty can foster students’ metacognition: supporting student learning strategies (i.e., study skills), encouraging monitoring and control of learning, and promoting social metacognition during group work.” They then “distill insights from key papers into general recommendations for instruction, as well as a special list of four recommendations that instructors can implement in any course.”

CBE Life Sci Educ June 1, 2021 20:fe3

Using Metacognition to Scaffold the Development of a Growth Mindset

by Lauren Scharff, PhD, U. S. Air Force Academy,*

Steven Fleisher, PhD, California State University,

Michael Roberts, PhD, DePauw University

It conceptually seems simple… inform students about the positive power of having a growth mindset, and they will shift to having a growth mindset.

If only it were that easy!

In reality, even if we (humans) cognitively know something is “good” for us, we may struggle to change our ways of thinking, behaving, and automatic emotional reactions because those have become habits. However, rather than throw up our hands and give up because it’s challenging, in this blog we will model a growth mindset by offering a new strategy to facilitate the transition to a growth mindset. The strategy involves metacognitive refection, specifically the use of awareness-oriented and self-regulation-oriented questions for both students and instructors.

Mindset Overview

To get us all on the same page, let’s first examine “mindset,” a term coined by Carol Dweck (2006). This concept proposes that individuals internalize ways of thinking about their abilities related to intelligence, learning, and academics (or any other skill). These beliefs become internalized based on years of living and hearing commentary about skills (e.g., She’s a born leader! or, You’re so smart! or, They are natural math wizzes!). These internalized beliefs subsequently affect our responses and performance related to those skills.

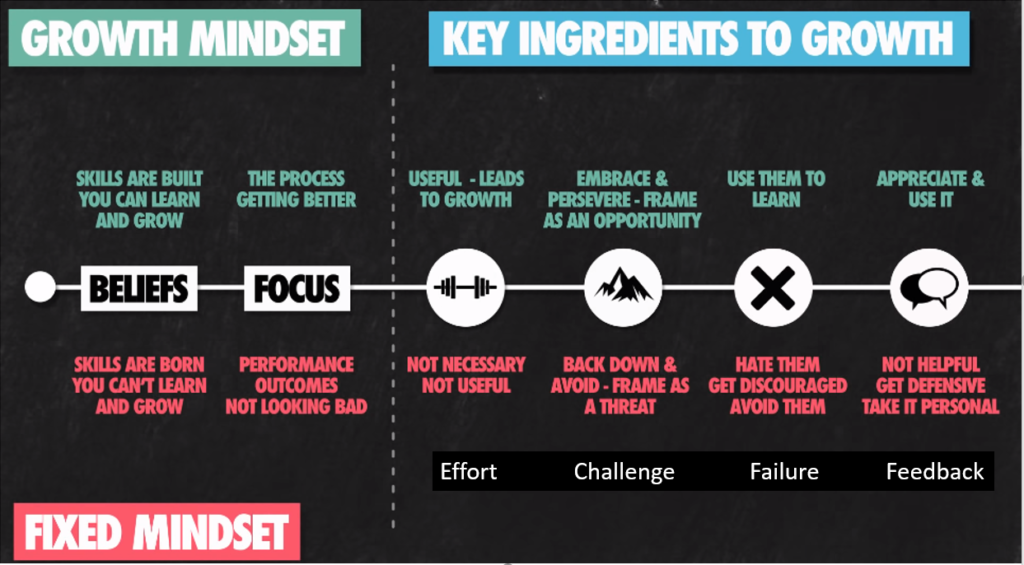

According to Dweck and others, people fall along a continuum (Figure 1) that ranges from having a fixed mindset (“My skills are innate and can’t be developed”) to having a growth mindset (“My skills can be developed”). Depending on a person’s beliefs about a particular skill, they will respond in predictable ways when a skill requires effort, when it seems challenging, when effort affects performance, and when feedback informs performance. The two-part mindset blog posts in Ed Nuhfer’s guest series (Part 1, and Part 2, 2022) provide evidence that the feedback component is especially influential.

Figure 1. Fixed – growth mindset tendencies. (From https://trainugly.com/portfolio/growth-mindset/)

Metacognition to Support Change

As the opening to this blog pointed out, simply explaining the concept of mindset and the benefits of growth mindset to students is not typically enough to lead students to actually adopt a growth mindset. This lack of change is likely even if students say they see the benefits and want to shift to a greater growth mindset. Thus, we need a process to scaffold the change.

We believe that metacognition offers a process by which to do this. Metacognition not only helps us examine our beliefs, but also provides a guide for one’s subsequent behaviors. More specifically, we believe metacognition involves two key processes, 1) awareness, often gleaned through reflection, and 2) self-regulation, during which the person uses that awareness to adjust their behaviors as needed in order to achieve their targeted goal.

Much research (e.g., Isaacson & Fujita, 2006) has already documented the benefits of students being metacognitive about their learning processes. However, we haven’t seen any other work focus on being metacognitive about one’s mindset.

Further, we know that efforts to develop skills are often more successful when they are more narrowly targeted on specific aspects of a broader construct (e.g., Heft & Scharff, 2017). Thus, rather than encouraging students to simply adopt a general “growth mindset,” or be metacognitive about their general mindset for a task, it would be more productive to target how they think about and respond to the specific component aspects of mindset for that task (e.g., challenge, feedback, failure).

Promoting a Growth Mindset Via Metacognition

Below we offer some example metacognitive reflection questions for students and for instructors that focus on awareness and self-regulation related to the feedback component of mindset. For the full set of questions that target all of the mindset components, please go to our full Mindset Metacognition Questions Resource.

We chose to highlight the component of feedback due to Nuhfer et al.’s findings reported in his 2022 guest series. By targeting the specific aspects of mindset, such as feedback, students might more effectively overcome patterns of thinking that keep them stuck in a fixed mindset.

We also include metacognitive reflection questions for instructors because they are instrumental in establishing a classroom environment that either supports or inhibits growth mindset in students. Instructors’ roles are important – recent research has demonstrated that instructor mindset about student learning abilities can impact student motivation, belongingness, engagement, and grades (Muenks, et al., 2020). Yeager, et al. (2021) additionally showed that mindset interventions for students had more impact if the instructors also display growth mindsets. Thus, we suggest that instructors examine their own behaviors and how those behaviors might discourage or encourage a growth mindset in their students.

Student Questions Related to Feedback

- (Self-assessment/awareness) How am I thinking about and responding to feedback that implies I need to make changes or improve?

- (Self-assessment/awareness) How am I interacting with the instructor in response to feedback? (emotional regulation; comfort versus frustration)

- (Self-regulation) How do I plan to respond to feedback I have / will receive?

- (Self-regulation) How might I reasonably seek feedback from peers or the instructor when more is needed?

Instructor Questions Related to Feedback

- (Self-assessment/awareness) Are students using my feedback? Are there aspects of content or tone of feedback that may be interacting with students’ mindsets?

- (Self-assessment/awareness) Am I appropriately focusing my feedback on student performance (e.g., meeting standards) rather than on students themselves (e.g. their dispositions or aptitudes)?

- (Self-regulation) When a student approaches me with a question, what do I signal via my demeanor? Am I demonstrating that engaging with feedback can be a positive experience?

- (Self-regulation) What formative assessments might I develop to provide students feedback about their progress and learn to constructively use that feedback to support their growth?

Take-aways and Future Directions

We believe the interconnections between mindset and metacognition can go beyond the use of metacognition to examine aspects of one’s mindset. Students can be metacognitive about the learning process itself, which can interact with mindset by providing realizations that adapting one’s learning strategies can promote success. The belief that one can try new strategies and become more successful is a hallmark of growth mindset.

We hope that you utilize the questions above for yourself and your students. Given the lack of research in this area, your efforts could make a contribution to the larger understanding of how to effectively promote growth mindset in students. (If you investigate, let us know, and we would welcome a blog post so you could share your results.) At the very least, such efforts might help students overcome patterns of thinking that keep them stuck in a fixed mindset, and it might help them more effectively cope with the inevitable challenges that they will face, both in and beyond the academic realm.

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Heft, I. & Scharff, L. (July 2017). Aligning best practices to develop targeted critical thinking skills and habits. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 17(3), pp. 48-67. http://josotl.indiana.edu/article/view/22600

Isaacson, R.M. & Fujita, F. (2006). Metacognitive knowledge monitoring and self-regulated learning: Academic success and reflections on learning. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 6(1), 39-55. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854910

Muenks, K., Canning, E. A., LaCosse, J., Green, D. J., Zirkel, S., Garcia, J. A., & Murphy, M. C. (2020). Does my professor think my ability can change? Students’ perceptions of their STEM professors’ mindset beliefs predict their psychological vulnerability, engagement, and performance in class. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(11), 2119-2114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000763

Yeager, D.S., Carroll, J.M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., Kersting, N., Hulleman, C., Kudym, M., Murphy, M., Duckworth, A.L., Walton, G.M., & Dweck, C.S.(2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18-32. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/09567976211028984

* The views expressed in this article, book, or presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Short-takes: Metacognition Ah-Ha Moments

Spring 2022: We asked folks, “What is your favorite metacognition “ah ha” moment that a student shared with you or you’ve experienced in the classroom?” Here are the responses:

- Randy Laist, “Stray Cats and Invisible Prejudices: A Metacognition Short-Take”

- Tara Beziat, “Is the driver really that far away?”

- Jennifer McCabe, “The Envelope, Please”

- Ritamarie Hensley, “Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages”

- Antonio Gutierrez de Blume, “Culture influences metacognitive phenomena”

- Kathleen Murray, “Metacognitive Thinking: A Mechanism for Change”

- Lindsay Byer, “Metacognition: Bringing Our Different Skills to the DEI Table”

- Gina R. Evers, “Vulnerability as a Connector”

- Ludmila Smirnova, “The Power of “Ah-ha Moments” in Collaboration”

- Marie-Therese C. Sulit, “Metacognition with Faith, Trust, and Joy in the Collaborative Process”

- Sonya Abbye Taylor, “What the World Needs Now: The Power of Collaboration”

Stray Cats and Invisible Prejudices: A Metacognition Short-Take

by Randy Laist, University of Bridgeport

We had reached the point in our freshman writing class where the students described the topics they were choosing for their research papers. Samara had a brilliant idea to conduct research inspired by the stray cats she had seen on campus. After praising the originality and perceptiveness that led her to propose this line of inquiry, I casually editorialized regarding what I thought everyone knew about stray cats: that they were “super-predators” that menaced birds and squirrels, laying waste to backyard ecologies. The other students followed my comments with their own observations and questions about stray cats, but I noticed that Samara seemed somehow crestfallen and remote.

The following week, we discussed the progress we had been making with our research, and, when it was Samara’s turn, she presented a catalog of evidence demonstrating that the stereotype of cats as super-predators is in fact completely erroneous. Stray cats, she explained, rarely eat birds and actually play an important role in controlling rodent populations, especially in cities. I couldn’t help but feel that she was directing this argument at me personally.

The perspective Samara supported through her research completely revolutionized what I thought I knew about stay cats, but, more fundamentally, her research confronted me with the invisibility of my own prejudices. So much of our lives and our thoughts consist of background “truths” that we acquire somehow at some point and that become an inert part of our mental architecture. They remain unquestioned, and they exert a constant influence on our thoughts and our behavior in ways that we rarely recognize. Samara’s independent thinking – the product of both her humanitarian principles and her academic inquiry – made me realize that I had been willing to believe terrible things about cats, even though I am myself a loving cat-owner. The experience made me feel more compassionate toward stray cats, more warry of my own perceived truths, and more appreciative of the role that academic research, observation-based inquiry, and interpersonal dialogue can play in challenging human beings to reprogram themselves for greater humility and empathy.

Is the driver really that far away?

by Tara Beziat, Auburn University at Montgomery

I had two female students who were great friends and happen to be in same class. One day when they were driving home from class, one pondered aloud if a sign on a truck was correct. It noted something about how the driver was x amount of feet away. As the two of them drove, they contemplated if the information on the truck was accurate. Something just didn’t seem right. They started to calculate the length of the truck. What they realized was they were using concepts we had learned in class that day to figure this “problem” out. They realized they were using critical thinking skills because they were objectively evaluating the information presented. But then as they realized what they were doing, they were also being metacognitive as thought about their thinking, as they drove down the road.

The Envelope, Please

by Jennifer McCabe, Goucher College

In my Human Learning and Memory course, my favorite metacognition “ah ha” moment comes during the final class period, when I return the sealed envelopes containing students’ first-day-of-class memories. On the first day, they record details about everything they have done in the past 24 hours, then mark routine (R) or novel (N) next to each event. They seal the written memories in an envelope, on which they write their names, and submit. (I promise to not open them.) During the final class, they try to remember as much as they can about that first day. Once they get started writing, I brandish the envelopes, at which point there are more than a few reactions along the lines of, “I totally forgot we did that!” and “I have no idea what I wrote!” As they are distributed, I suggest that just seeing the envelope can be an effective retrieval cue. Finally, the big metacognitive moment – opening the envelopes to discover what they wrote that first day! The reactions at this point are mostly along the lines of disbelief that they wrote so much more than they can remember now. This leads to a discussion of transience, and how they now have very personal evidence of how much we forget about our own lives. We also discuss episodic versus semantic elements of their memories, and whether routine or novel elements tended to be remembered best. I conclude with anti-transience strategies, such as keeping a journal or using social media to document life events.

Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages

by Ritamarie Hensley, Simmons University

After teaching at the high school level for many years, I knew students didn’t read the directions, finish assignments on time, or know how to write a coherent paragraph. Of course, these characteristics didn’t describe all of my students, but I often encountered these issues from year-to-year. So when I began teaching doctoral students for the first time, I assumed I would not need to worry about them turning-in late papers, writing illogical paragraphs, or ignoring my instructions.

Hence the aha moment.

Students are students and no matter what their age or level of education, they need me. They need me to teach the basics of writing a coherent paragraph. They need me to remind them when a paper is due. And, they need me to point out the directions… again. But, that’s okay. It’s what I do. Teaching is teaching at all levels and people are people at all ages. Whether it’s earning a high school diploma or a terminal degree, people are busy and human, so they need their instructors to help them attain their goals, even if that means reminding them of the directions one more time.

Culture influences metacognitive phenomena

by Antonio Gutierrez de Blume, Georgia Southern University

What is “metacognition”? What does it mean to experience or become aware of one’s own thoughts? Since John Flavell coined the term in 1979, metacognition has been colloquially understood as thinking about one’s own thinking or taking one’s own thoughts as the object of cognition. However, this definition is far from complete because, among other things, it assumes, without actual evidence, that metacognition is a universal construct that is consistently experienced by all people. Nevertheless, I began to think more deeply on this matter and decided it was time to empirically examine the homogeneity or heterogeneity of metacognition across cultures and languages of the world rather than make wholesale assumptions.

In a recent study with 366 individuals across four countries (China, Colombia, Spain, US) and three languages (Chinese, English, Spanish), a group of colleagues and I investigated the influence of culture on metacognitive awareness (subjective) and objective metacognitive monitoring accuracy. We discovered, much to our surprise, that metacognition is not a homogenous concept or experience. In other words, metacognitive phenomena are understood and experienced differently as a function of the cultural norms and expectations in which one is reared. Imagine that! Future qualitative research will hopefully help us understand why and how culture influences metacognitive phenomena, including among indigenous populations of the world.

If you had asked me 5 years ago where my research on metacognition would take me, I would have never believed it would be down this path. However, I am excited about the prospect of continuing down the path of intercultural/multicultural investigation of metacognition!

Metacognitive Thinking: A Mechanism for Change

by Kathleen Murray, Mount Saint Mary College

Pushing us to reflect and evaluate our own personal strengths and limitations, Chick defines metacognition as “the processes used to plan, monitor, and assess one’s understanding and performance” (2013). Metacognition allows us to recognize the limitations of our knowledge and encourages us to figure out how to expand our ways of thinking and extend our abilities. There is no better example of this principle in action than Mount Saint Mary College’s DEI Dream Team: a group of individuals from all different walks-of-life united in our common desire to expand our perspective and make a difference in the community. Inspired by Tell Me Who You Are, our Dream Team created a series of workshops designed to promote reflection and educate both faculty and staff on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Our moniker, “Dream Team,” was, in fact, coined after an “ah-ha” moment when I first recognized the unique nature of this collaboration. These team members pushed me to expand my way of thinking and facilitated my growth as both an individual and a future educator. As I sit here and reflect on the success of these workshops, I am overwhelmed by the power of metacognitive thinking and inspired by the difference that our group could make in the campus community. After experiencing this wonderful collaboration rooted in parity, I now understand that metacognition is more than a pedagogical process or professional concept. It is a powerful tool that can be used to inspire activism and change the world.

Reference:

Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved January 22, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/metacognition/.

Metacognition: Bringing Our Different Skills to the DEI Table

by Lindsay Byer, Mount Saint Mary College

I remember being in one of our virtual planning meetings when my “Ah-ha” moment clicked. I was surrounded by women who were, and still are, inspiring in their own right. There are six of us: two undergraduate students, including myself, two Education professors, one professor from Arts and Letters, and the Director of the Writing Center. Each of us brought different skills to the metaphorical table along with different perspectives on how to best achieve our goal of spreading awareness of diversity, equity, and inclusion on our campus. I was nervous, to say the least, but I quickly realized I was being heard! My opinions carried the same weight as everyone else in that meeting. This was an atypical experience for me in working with faculty.

Met with collective positivity, I kicked off the forum series with a workshop focusing on the individual’s identity. Knowing the importance of creating a safe space for all participants, I used vignettes from Tell Me Who You Are to introduce terms, like intersectionality, and I closed with the opportunity to create “I am” poems. At some point during our planning process, and after Katie coined it, we referred to ourselves as the Dream Team, which couldn’t have suited us more. We were able to collaborate with respect towards one another, support one another, and allow one another to lead. I learned so much from working with these women and I am proud to say I am a member of the Dream Team.

Vulnerability as a Connector

by Gina R. Evers, Mount Saint Mary College

I have worked in academia my whole career, and I am cognizant of the invisible lines of power that have traditionally defined relationships among students, professors, and administrators. In our collaboration, however, we were able to create genuine, equal relationships across these boundaries. And it seemed to happen without intentional effort. How? What allowed this “committee” to disregard our institutionally prescribed guardrails with ease?

When facilitating “Writing Through a Racial Reckoning,” I included a read aloud of Ibram X. Kendi’s Antiracist Baby. Dr. Kendi encourages us to “confess” after realizing we may have done something racist. I remember the burn of shame I felt the first time I encountered this methodology. But as an educator, I knew that if I was experiencing such a strong reaction, it’s likely some of my students were as too. I shared and acknowledged that talking about mistakes and questions moves us forward while silence upholds racist structures. Through making myself vulnerable, I was able to create a brave space for workshop participants and invite folks to share on genuine and equal terms.

The fact that our “committee,” comprised of people occupying different institutional roles with inherently varying power structures, was able to achieve parity in our collaboration was enabled by our union in DEI work. Discussions of our common text — sharing our vulnerabilities around the content and genuinely grappling with matters of identity — connected us as equal members of a team, poised to rise together.

The Power of “Ah-ha Moments” in Collaboration

by Ludmila Smirnova, Mount Saint Mary College

One of the most memorable experiences and pedagogical discoveries of the last year was the work of our Dream Team on a college-wide initiative around issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The first “ah-ha moment” was when a spontaneous group of diverse but like-minded people gathered together to collaborate on the design and implementation of the project. It was amazing to interact with teacher candidates and faculty from other divisions and offices outside of the traditional college classroom. What united us was our devotion to the importance of DEI on campus and the desire to bring this project to its success. The college chose an excellent book, Tell Me Who You Are, for a common read and the team voluntarily met to discuss and implement a series of workshops to engage college students and faculty in activities that centered the content of the book. That’s the power of metacognition—being aware of how to plan events, choosing strategies for implementing the ideas, and reflecting on them collectively. Our students experienced the “ah-ha moments” a number of times throughout this project. How captivating to observe how mesmerized our students were to communicate with their faculty and how grateful they were to see that their voices counted and that they were able to contribute their ideas to the project as equal partners! But the most astonishing outcome of this project was our team collaboration on the book chapter that allowed us to reflect on this experience in a series of personal vignettes.

Metacognition with Faith, Trust, and Joy in the Collaborative Process

by Marie-Therese C. Sulit, Mount Saint Mary College

As I choose a favorite metacognition moment, two simultaneous experiences capture that sense of “ah-ha!” for me: when we first came together as a planning team and when we met for our penultimate writing workshop for our book chapter. In Tell Me Who You Are, I found the plethora of vignettes so well rendered with storytelling so ripe and rich to address our DEI initiative that I envisioned a series of “Talk Story” and “Talk Pedagogy” workshops. Our Dream Team came together in answering this call that created and delivered a forum series for our campus. While not easy, it certainly seemed so as we almost intuitively balanced and counter-balanced one another through every step of this process: preparation, execution, reflection. This collaboration then brought a book chapter to life, requiring a series of writing workshops every Friday afternoon throughout the fall semester. In contradistinction to the forum series, the nature of and expectations for publication moved us in different directions with a deadline after the Thanksgiving holiday. All of us, in our respective roles, were likewise closing our semesters. So important to us, this commitment stretched us in ways that we had not been stretched: it was all in the timing. However, with this all-female cast, the mutual reciprocity of our collaboration–the teaching/learning, problem-solving and shared decision-making–remained the same but especially worked through our commitment to metacognition. In so doing, we also affirmed our sense of faith, trust, and joy in the process and with one another.

What the World Needs Now: The Power of Collaboration

by Sonya Abbye Taylor, Mount Saint Mary College

I saw pride in my students’ expressions when they completed a beautifully executed collaborative course project. They agreed each contributed to the success of the project: they were joyful! Brought back to a moment, the semester before, I felt that same joy and awe at an Open Mic session, the culminating event of a collaborative venture, I worked on with students and faculty. We created a series of workshops addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion. While the workshops were excellent, it was the collaborative process that impacted me as being the most meaningful, just as it was for those students. Wide in age-range, from different ethnicities, different backgrounds and frames of reference, our diverse group—two undergraduates, two Education faculty, one Arts and Letters faculty member, and the Director of the Writing Center—functioned as true collaborators. We had parity, as everyone’s ideas weighed equally, we listened actively and empathetically to one another, and we communicated effectively. Committed to a common goal, and having achieved it beyond our expectations, I knew at that “ah ha” moment something very special had happened. I knew, without having been taught the aforementioned skills essential for effective collaboration, we had been successful. I realized the power of collaboration and bemoaned the lack of opportunities to practice collaboration in schools. When we teach collaboration, we teach skills for life. I learn and contribute when I collaborate; I want my students do the same. People, willing and able to collaborate, can change the world.

*Reference:

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Vocational and Adult Education. (2011). Just Write! Guide. Washington, DC

What’s Metacognition—and Why Does it Matter?

This short video by Edutopia shares seven questions to ask to encourage metacognition in students.

Metacognition: The Skill That Promotes Advanced Learning

This video provides a great overview of metacognition to support student learning, including several metacognitive questions students can ask themselves as they go through different stages of learning (prior to learning, as learn, after learning).

Metacognition Activities & Strategies: The Ultimate Guide

This Ultimate Guide webpage put together by Global Metacognition shares 40 metacognition activities and teaching strategies, along with short descriptions of each.

U.S. Army Cadets and Faculty Reflecting on a Metacognitive Assignment from a General Education Writing Class

by Brody Becker, Jack Curry, Charlie Gorman, Caleb Norris, J. Michael Rifenburg, and Erik Siegele

We offer an assignment from a general education writing class that invites students to hone their metacognitive knowledge by, oddly enough, writing about writing. Before we turn to this assignment, we need to detail who we are. We are a six-person author team. Five of us are first-year U.S. Army cadets. All five plan to commission into the U.S. Army following graduation. One of us is a civilian, tenured professor in the English Department.

During the Fall 2021 semester, we met in English 1102, a general education writing class offered at the University of North Georgia (UNG). Our university is a federally designated senior military college, like Texas A&M and The Citadel, tasked with educating future U.S. Army officers. Civilians also attend UNG. At our school, roughly 700 cadets learn alongside roughly 20,000 civilian undergraduate students. These details are important to what we want to describe in this post: not only a metacognitive writing assignment for this specific class but also the perspective of cadets who completed this assignment and the value of such metacognitive work for cadets. We write as a six-person team and offer collective ideas (as we do in this paragraph). However, we also value individual perspective. Author order is alphabetical and does not signal one writer contributing more than another writer.

During the Fall 2021 semester, we met in English 1102, a general education writing class offered at the University of North Georgia (UNG). Our university is a federally designated senior military college, like Texas A&M and The Citadel, tasked with educating future U.S. Army officers. Civilians also attend UNG. At our school, roughly 700 cadets learn alongside roughly 20,000 civilian undergraduate students. These details are important to what we want to describe in this post: not only a metacognitive writing assignment for this specific class but also the perspective of cadets who completed this assignment and the value of such metacognitive work for cadets. We write as a six-person team and offer collective ideas (as we do in this paragraph). However, we also value individual perspective. Author order is alphabetical and does not signal one writer contributing more than another writer.

An Overview of this Metacognitive Assignment

I (Michael) regularly teach this general education writing class. One writing assignment opened with the following prompt: “For this second paper, I invite you to reflect on a previous paper you wrote during your college or high school career. Through detailing when and where you wrote the paper, the processes you undertook to write the paper, and the feedback or grade you received on this paper, you will make a broader argument about the importance of reflecting back on writing and lessons one learns from undertaking such reflection.” This assignment is a modified version of a similar writing assignment in Wardle and Downs’s (2014) popular textbook Writing About Writing.

To prepare to write this paper, we read the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing,” a national consensus document outlining, as the title suggests, a framework for students to succeed at college level writing. This document offers eight habits of mind essential for student-writers to hone: one of these habits of mind is metacognition. We also read through portions of Tanner’s (2017) “Promoting Student Metacognition.” Tanner provided a table of metacognitive questions instructors can ask students before, during, and after the course.

Students then wrote a 1,500 word essay in response to this assignment. All student co-authors for this blog post enrolled in this specific class and completed this assignment. I now turn to my co-authors, cadet Charlie Gorman and cadet Brody Becker, to hear their perspectives on this assignment.

Cadets’ Reflections

Charlie’s reflection on this metacognitive assignment

I found that this assignment was beneficial to grow as a writer. Reflecting back on activities or assignments is a great way to improve in any aspect of life. I would have never thought about writing a paper about a paper until I was given the opportunity to write this assignment. As a future leader in the military, my writing will consist of educating material, reports, and special directions. Completing this assignment has set me up and taught me how to use past failures and successes to improve upon a future performance.

Brody’s reflection on this metacognitive assignment

This paper on metacognition was difficult for me because I had never done anything along these lines in a writing aspect previously. However, I soon found it to be helpful because of all the things I could learn from and look for in future writing. I had never thought about how looking back at previous writing could be helpful to me, so I always disregarded any past assignments and never thought about them again. This was a teaching moment for me, and I always take chances to learn new things. This assignment was one of the more beneficial things that I have done that I will continue to use for future assignments and will carry over to other things in life.

Why such an assignment is particularly helpful for cadets

In this section, Cadet Jack Curry considers why such a metacognitive writing assignment is particularly helpful for cadets who, after graduation, will commission as officers in the U.S. Army.

As a cadet, metacognition is an important step for our future progress. Being able to review and learn from our mistakes and our successes, helps us become better leaders. After any exercise or training, we conduct After Action Reviews (AARs) to find out how we can either improve upon or continue upon our training. As future officers, our job is to continue improving the skills we will use to lead future soldiers. The U.S. Army’s publication Training Circular 25-20: A Leader’s Guide to After Action Reviews (1993), states “the reason we conduct AARs are in order to find candid insights into specific soldier, leader, and unit strengths and weaknesses from various perspectives, and to find feedback and insight critical to battle-focused training.”

Concluding words of hope for more faculty-student partnerships

Our partnership started as a teacher-student one. Michael designed writing assignments and led classroom activities, and Charlie, Caleb, Jack, Brody, and Erik completed writing assignments and completed classroom activities. Near the end of the semester, our partnership shifted into one of co-authors where we wrote this blog post together over Google Docs, bounced ideas back and forth in-person after class, and coordinated further over email. We use the noun partnership intentionally to signal our commitment to pedagogical partnerships, an international and interdisciplinary movement to re-see the student-faculty relationship as one in which both serve as active agents in curriculum design, implementation, and assessment (e.g., Cook-Sather et al., 2019). As readers of and contributors to Improve with Metacognition continue to explore the benefits of structured metacognitive tasks throughout higher education, we hope that undergraduate students are at the forefront of this exploration. Partnerships between faculty and students are one productive step to ensuring that our classroom practices and processes best serve all our students.

References

Cook-Sather, A., Bahti, M., & Ntem, A. (2019). Pedagogical partnerships: A how-to guide for faculty, students, and academic developers in higher education. Elon University’s Center for Engaged Learning Open Access Book Series. Retrieved from https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/books/pedagogical-partnerships/

Council of Writing Program Administrators et al. (2011). “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing.” Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

U.S. Department of the Army. (1993). Training Circular 25-20: A Leader’s Guide to After Action Reviews. Army Publishing Directorate. Retrieved from https://armypubs.army.mil/productmaps/pubform/details.aspx?pub_id=71643

Tanner, K. (2017). Promoting student metacognition. Life Sciences Education, 11(2). Retrieved from https://www.lifescied.org/doi/full/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033

Wardle, E., & Downs, D. (2014). Writing About Writing: A College Reader. 2nd ed. Bedford.

Promoting Learning Integrity Through Metacognition and Self-Assessment

by Lauren Scharff, Ph.D., U. S. Air Force Academy*

When we think of integrity within the educational realm, we typically think about “academic integrity” and instances of cheating and plagiarism. While there is plenty of reason for concern, I believe that in many cases these instances are an unfortunate end result of more foundational “learning integrity” issues rather than deep character flaws representing lack of moral principles and virtues.

Learning integrity occurs when choices for learning behaviors match a learner’s goals and self-beliefs. Integrity in this sense is more like a state of wholeness or integrated completeness. It’s hard to imagine this form of integrity without self-assessment; one needs to self-assess in order to know oneself. For example, are one’s actions aligned with one’s beliefs? Are one’s motivations aligned with one’s goals? Metacognition is a process by which we gain awareness (self-assess) and use that awareness to self-regulate. Thus, through metacognition, we can more successfully align our personal goals and behaviors, enhancing our integrity.

Learning integrity occurs when choices for learning behaviors match a learner’s goals and self-beliefs. Integrity in this sense is more like a state of wholeness or integrated completeness. It’s hard to imagine this form of integrity without self-assessment; one needs to self-assess in order to know oneself. For example, are one’s actions aligned with one’s beliefs? Are one’s motivations aligned with one’s goals? Metacognition is a process by which we gain awareness (self-assess) and use that awareness to self-regulate. Thus, through metacognition, we can more successfully align our personal goals and behaviors, enhancing our integrity.

Metacognitive Learning and Typical Challenges

When students are being metacognitive about their learning, they take the time to think about (bring into awareness) what an assignment or task will require for success. They then make a plan for action based on their understanding of that assignment as well their understanding of their abilities and current context. After that, they begin to carry out that plan (self-regulation). As they do so, they take pauses to reflect on whether or not their plan is working (self-awareness/self-assessment). Based on that interim assessment, they potentially shift their plan or learning strategies in order to better support their success at the task at hand (further self-regulation).

That explanation of a metacognitive learning may sound easy, but if that were the case, we should see it happening more consistently. As a quick example, imagine a student is reading a text and then realizes that they are several pages into the assignment and they don’t remember much of what they’ve read (awareness). If they are being metacognitive, they should come up with a different strategy to help them better engage with the text and then use that alternate strategy (self-regulation). Instead, many students simply keep reading as they had been (just to get the assignment finished), essentially wasting their time and short-cutting their long-term goals.

Why don’t most students engage in metacognition? There are several meaningful barriers to doing so:

- Pausing to self-assess is not a habitual behavior for them

- It takes time to pause and reflect in order to build awareness

- They may not be aware of effective alternate strategies

- They may avoid alternate strategies because they perceive them to take more time or effort

- They are focused on “finishing” a task rather than learning from it

- They don’t realize that some short-term reinforcements don’t really align with their long-term goals

These barriers prevent many students engaging in metacognition, which then makes it more likely that their learning choices are 1) not guided by awareness of their learning state and 2) not aligned with their learning goals and/or the learning expectations of the instructor. This misalignment can then lead to a breakdown of learning integrity with respect to the notion of “completeness” or “wholeness.”

For example, students often claim that they want to develop expertise in their major in order to support their success in their future careers. They want to be “good students.” But they take short-cuts with their learning, such as cramming or relying on example problem workout steps, both of which lead to illusions of learning rather than deep learning and long-term retention. These actions are often rewarded in the short term by good grades on exams and homework assignments. Unfortunately, if they engage in short-cutting their learning consistently enough, when long-term learning is expected or assessed, some students might end up feeling desperate and engage in blatant cheating.

Promoting Learning Integrity by Providing Support for Self-Assessment and Metacognition

Promoting learning integrity will involve more than simply encouraging students to pause, self-reflect, and practice self-regulation, i.e. engage in metacognition. As alluded to by the list of barriers above, being metacognitive requires effort, which also implies that learning integrity requires effort. Like many other self-improvement behaviors, developing metacognition requires multiple opportunities to practice and develop into a way of doing things.

Fortunately, as instructors we can help provide regular opportunities for reflection and self-assessment, and we can share possible alternative learning strategies. Together these should promote metacognition, leading to alignment of goals and behaviors and to increased learning integrity. The Improve with Metacognition website offers many suggestions and examples used by instructors across the disciplines and educational levels.

To wrap up this post, I highlight knowledge surveys as one way by which to promote the practice and skill of self-assessment within our courses. Knowledge surveys are shared with students at the start of a unit so students can use them to guide their learning and self-assess prior to the summative assessment. Well-designed knowledge survey questions articulate granular learning expectations and are in clear alignment with course assessments. (Thus, their implementation also supports teaching integrity!)

When answering the questions, students rate themselves on their ability to answer the question (similar to a confidence rating) as opposed to fully writing out the answer to the question. Comparisons can be made between the confidence ratings and actual performance on an exam or other assessment (self-assessment accuracy). For a more detailed example of the incorporation of knowledge surveys into a course, as well as student and instructor reflections, see “Supporting Student Self-Assessment with Knowledge Surveys” (Scharff, 2018).

By making the knowledge surveys a meaningful part of the course (some points assigned, regular discussion of the questions, and sharing of students’ self-assessment accuracy), instructors support the development of self-assessment habits, which then provide a foundation to metacognition, and in turn, learning integrity.

———————————————–

* Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U. S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Govt.

Learning in Pandemic Times

In this video, Dr. Stephen Chew shares a model about how people learn, and highlights key points about memory that will benefit students as they are trying to learn and cope, especially in stressful times like we are experiencing with the Covid pandemic.

Critically Thinking about our Not-So-Critical Thinking in the Social World

By Randi Shedlosky-Shoemaker and Carla G. Strassle, York College of Pennsylvania

When people fail to engage in critical thinking while navigating their social world, they inevitably create hurdles that disrupt their cultural awareness and competence. Unfortunately, people generally struggle to see the hurdles that they construct (i.e., bias blind spot; Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002). We propose metacognition can be used to help people understand the process by which they think about and interact with others.

The first step is to reflect on existing beliefs about social groups, which requires people to examine the common errors in critical thinking that they may be engaging in. By analyzing those errors, people can begin to take down the invisible hurdles on the path to cultural awareness and competency. Using metacognition principles collected by Levy (2010), in this post we discuss how common critical thinking failures affect how people define and evaluate social groups, as well as preserve the resulting assumptions. More importantly, we provide suggestions on avoiding those failures.

Defining Social Groups

Social categories, by their very nature, are social constructs. That means that people should not think of social categories in terms of accuracy, but rather utility (Levy, 2010, pp. 11-12). For example, knowing a friend’s sexual orientation might help one consider what romantic partners their friend might be interested in. When people forget that dividing the world into social groups is not about accurately representing others but rather a mechanism to facilitate social processes, they engage in an error known as reification. In relation to social groups, this error can also involve using tangible, biological factors (e.g., genetics) as the root cause of social constructs (e.g., race, gender). To avoid this reification error, people should view biological and psychological variables as two separate, but complementary levels of description (Levy, 2010, pp. 15-19), and remember that social categories are only important if they are useful.

Beyond an inappropriate reliance on biological differences to justify the borders between social groups, people often oversimplify those groups. Social categories are person-related variables, which are best represented on a continuum; reducing those variables to discrete, mutually exclusive groups, creates false dichotomies (Levy, 2010, pp. 26-28). False dichotomies, such as male or female, make it easier to overlook both commonalities shared by individuals across different groups as well as differences that exist between members within the same group.

Overly simplistic dichotomies also support the assumption that two groups represent the other’s polar opposite (e.g., male is the polar opposite of female, Black is the polar opposite of White). Such an assumption means ignoring that individuals can be a member of two supposedly opposite groups (e.g., identify as multiple races/ethnicities) or neither group (e.g., identify as agender).

Here, metacognition promotes reflection on the criteria used for defining group memberships. In that reflection, people should consider whether the borders that they apply to groups are too constraining, leading them to misrepresent individuals with whom they interact. Additionally, people should consider ways in which seemingly different groups can have shared features, while also still maintaining some degree of uniqueness (i.e., similarity-uniqueness paradox, Levy, 2010, pp. 39-41). By appreciating the nature and limitations of the categorization process, people can reflect upon whether applications of group memberships are meaningful or not.

Evaluating Social Groups

Critical thinking failures that occur when defining social categories are compounded when people move from describing social groups into evaluating those social groups (i.e., evaluative bias of language, Levy, 2010, pp. 4-7). In labeling social others, people often speak to what they have learned to see as different. As more dominant groups retain the power to set the standards, people may learn to use the dominant groups as the default (i.e., cultural imperialism; Young, 1990). For example, when people describe others as “that older woman”… “that kid”… “that blind person”… and so on – their chosen label conveys what they see as divergent from the status quo. By becoming more aware of the language they use, people simultaneously become more aware of how they think about social others based on social grouping. In monitoring and reflecting on language, metacognition affords us a valuable opportunity to adapt thinking through language.

Changing language can be challenging, however, particularly when people find themselves in environments that lack diversity. Frequently, people find themselves surrounded by others who look, think, and act like them. When surrounded by others who largely represent one’s self, unreflective attempts to make sense of the world may naturally echo their point of view. This is problematic for two reasons: first, people tend to rely more on readily available information in decision-making and judgments (i.e., availability heuristic, Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

Further, with one’s own views reflected back at them, people easily overestimate how common their beliefs and behaviors are (i.e., false consensus effect, Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). That inaccurate assessment of “common” can lead people to conclude that such beliefs and behaviors are also “good”. Conversely, what is seen as different or uncommon, relative to the self, becomes “bad” (i.e., naturalistic fallacy, Levy, 2010, pp. 50-51).

By pausing to assess the variability of perspectives people have access to, metacognition allows people to consider what perspectives they are missing. In that way, people can more intentionally seek out ideas and experiences that may be different from their own.

Preserving Assumptions

Though not easy, breaking away from one’s point of view and seeking out diverse perspectives can also address another hurdle that people create for themselves: specifically, the tendency to preserve one’s existing assumptions (i.e., belief perseverance phenomenon; e.g., Ross & Anderson, 1982). Change takes work, and not surprisingly, people often choose the path of least resistance – that is, to make new information fit into the system we already have (i.e., assimilation bias, Levy, 2010, pp. 154-156).

Further, people tend to seek out information that supports existing beliefs while disregarding or discounting disconfirming information (i.e., confirmation bias, Levy, 2010, pp. 164-165). Given the habit of sticking to what fits with existing beliefs, people develop an illusion of consensus. Existing beliefs are reinforced when people fail to realize that such beliefs inadvertently influence behaviors, which in turn shape interaction, thereby creating situations that further support, rather than challenge, existing belief systems (i.e., self-fulfilling prophecy, e.g., Wilkins, 1976).

This tendency then, to protect what one already “knows” speaks to the necessity of metacognition to challenge one’s existing belief system. When people analyze and question their existing beliefs they can begin to recognize where revision of those existing beliefs is needed and choose to acquire new perspectives to do so.

Summary

So many of the critical thinking failures above occur without much effortful or conscious awareness on our part. Engaging in metacognition, and non-defensively addressing the unintentional errors one makes, allows people to break down common hurdles that disrupt cultural awareness and competency. It’s when people critically reflect upon their thought processes, identifying the potential errors that may have shaped their existing perspectives, that they can begin to change how they think and feel about social others. In terms of developing a heightened sense of cultural awareness and competency, metacognition then helps us all realize that the world is a much more complex though interesting place.

References

Levy, D.A. (2010). Tools of critical thinking: Metathoughts for psychology. Waveland Press.

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 369-381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202286008

Ross. L., & Anderson, C. (1982). Shortcomings in the attribution process: On the origins and maintenance of erroneous social assessments. In D. Kahneman, P. Siovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Cambridge Univ. Press.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977).The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 27, 1124-1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

Wilkins, W. E. (1976). The concept of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Sociology of Education, 49, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.2307/2112523

Young, I. (1990). Justice and the politics of difference. Princeton University Press.

To Infinity and Beyond: Metacognition Outside the Classroom

by Kyle E. Conlon, Ph.D., Stephen F. Austin State University

My wife, Lauren, and I met in graduate school while pursuing our doctoral degrees in social psychology. Since then, we’ve taught abroad in London, moved to two different states, landed jobs at the same institution—our offices are literally right next to each other’s—bought a house, and had a child. It’s fair to say that our personal and professional lives interweave. One of the great joys of having an academic partner is having someone with whom I can share the challenges and triumphs of teaching. Although we have long promoted the benefits of metacognition in our classrooms, we use metacognition in so many other domains of our lives as well. But the link between metacognitive practice in the classroom and real-world problem solving isn’t always clear for students.

In this post, I’ll discuss how facilitating metacognition among your students can benefit them long after they’ve finished your class, with an emphasis on two important life goals: financial planning and healthy eating.

Metacognition and Money

At first glance, a college student may find little connection between thinking about his or her test performance in an introductory psychology class and building a well-diversified investment portfolio years later. But the two are more intimately linked than they appear. Students who possess high metacognitive awareness are able to identify, assess, and reflect on the effectiveness of their study strategies. This process requires the development and cultivation of accurate self-assessment and self-monitoring skills (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009). As teachers, then, we serve as primary stakeholders in our students’ metacognitive development.

Just as successful students think about their own thinking, successful investors spend a lot of time thinking about how to manage their money—how to invest it (stocks, bonds, REITs, etc.), how long to invest it, how to reallocate earnings over time, and so on. Smart investing is virtually impossible without metacognition: it requires you to continually assess and reassess your financial strategies as the markets move and shake.

Even if your students don’t plan on being the next Warren Buffet, financial thinking will play a central role in their lives. Budgeting, buying a house or a car, saving for retirement, paying off debt—all of these actions require some level of financial literacy (not to mention self-control). Of course, I’m not saying that students need a degree in finance to accomplish these goals, just that they are more easily attainable with strong metacognitive skills.

Indeed, financial security is elusive for many; for instance, the 2018 Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households found that many adults would struggle with a modest unexpected expense. There are real financial obstacles that families face, for sure. Because financial literacy has broad implications, from participation in the stock market (Van Rooj et al., 2011) to retirement planning (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2007), the transfer of metacognitive skills from academic to financial decisions may be especially paramount.

Admittedly, when I was an 18-year-old college student, I didn’t think much about this stuff. (I was too busy studying for my psychology exams!) But now, years later, living on a family budget, I have a deep appreciation for how the metacognitive awareness I cultivated as a student prepared me to think about and plan for my financial future. For your students, the exams will end, but the challenges of adulthood lie ahead. Successfully navigating many of these challenges will require your students to be metacognitive about money.

Metacognition and Food

As with planning for one’s financial future, eating healthy food is a considerable challenge that involves tradeoffs: Do I eat the salad so I can keep my cholesterol low, or do I enjoy this piece of delicious fried chicken right now, cholesterol be damned? Anyone who’s ever struggled with eating healthy food knows that peak motivation tends to occur shortly after committing to the goal. You go to the grocery store and buy all the fruits and vegetables to replace the unhealthy food in your fridge, only to throw away most of it later that same week. Why is eating healthfully so difficult?

There is an important role for metacognition here. When I teach my Health Psychology students about healthy eating, I draw the habit cycle on the whiteboard: cue à routine à reward (Duhigg, 2012). I tell students that breaking a bad habit requires changing one piece of the cycle (routine). Keep the cue (“I’m hungry”) and the reward (“I feel good”) the same, just change the routine from mindlessly eating a bag of potato chips to purposefully eating an apple. Implicit in this notion is the need to be aware of what you’re eating and the benefits of doing so—in other words, metacognition. Another idea is to have students draw out their steps through the grocery store so they can see which aisles they tend to avoid and which aisles they tend to visit (the ones with processed food). Students gain metacognitive awareness by literally retracing their steps.

In college, I survived on sugar, sugar, and more sugar. (One category short of Buddy the Elf’s four main food groups.) Since then, my metabolism has slowed considerably. Fortunately, with the help of metacognition, I’ve changed my diet for the better. I also cook most meals for our family, so I’m constantly thinking about meal plans, combinations of healthy ingredients, and so on. For me, as for many people, healthy eating didn’t occur overnight; it was a long process of habit change aided by awareness and reflection of the food I was consuming. The good news for your students is that they have several opportunities every day to think intently about their food choices.

The Broad Reach of Metacognition

As a teacher, I love those “lightbulb” moments when a student makes a connection that was previously unnoticed. In this post, I’ve tried to connect metacognition in the classroom to two important life domains. By fostering metacognition, you’re indirectly and perhaps unknowingly teaching your students how to make sound decisions about their finances and eating habits—and probably hundreds of other important life decisions. Metacognition is not limited to exam grades and paper rubrics; it’s not confined to our classrooms. It’s one of those special, omnipresent skills that will help students flourish in ways they’ll never see coming.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2019). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2018. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2018-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201905.pdf

Duhigg, C. (2012). The power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. Random House.

Dunlosky, J., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Sage Publications, Inc.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education. Business Economics, 42(1), 35‒44.

Van Rooj, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449‒472.

Micro-Metacognition Makes It Manageable

By Dr. Lauren Scharff, U. S. Air Force Academy *

For many of us, this time of year marks an academic semester’s end. It’s also intertwined with a major holiday season. There is so much going on – pulling our thoughts and actions in a dozen different directions. It almost seems impossible to be metacognitive about what we’re doing while we’re doing it: grading that last stack of exams or papers, finalizing grades, catching up on all those work items that have been on the back burner but need to get done before the semester ends. And that’s just a slice of our professional lives. Add in all the personal tasks and aspirations for these final few weeks of the year, and it’s Go, Go, Go until the day is over.

Well, that was a bit cathartic to get out, but also a bit depressing. Logically I know that by taking the time to reflect and use that awareness to help guide my behaviors (i.e. engage in metacognition), I will feel energized and revitalized because I’ll have a plan with a good foundation. I will more likely be successful in whatever it is I’m hoping to accomplish, especially if I regularly take the time to reflect and fine tune my efforts. But the challenge is, how do I fit it all in?

My proposed solution is micro-metacognition!

So, what do I mean by that? I think micro-metacognition is analogous to taking the stairs whenever you can rather than signing up for a new gym membership. Stairs are readily available at no cost and can be used spur-of-the-moment. In comparison, the gym membership requires a more concerted effort and larger chunks of time to get to the facility, work out, clean up and head home. In the more academic realm, micro metacognition falls in line with the spirit of James Lang’s (2016) Small Teaching recommendations. He advocates for the powerful impact of even small changes in our teaching (e.g. how we use the first 5 minutes of class). In other words, we don’t have to completely redesign a course or our way of teaching to see large benefits.

To help place micro-metacognition into context, I will borrow a framework from Poole and Simmons (2013), who suggested a “4M” model for conceptualizing the level of impact of SoTL work: micro (individual/classroom), meso (department/ program), macro (institutional), and mega (beyond a single institution). In this case though, we’re looking at engagement in metacognitive practices, so the entity or level of focus will always be the individual, and the scale will refer to the amount of planning, effort, and time needed for the metacognitive practice. This post focuses on instructors being metacognitive about their practice of teaching, but I believe that parallels can easily be made for students’ engagement in metacognition as they are learning.

The 4M Metacognition Framework

Micro-metacognition – Use of isolated, low-cost tactics to promote metacognitive instruction when engaged in single tasks (e.g. grading a specific assignment – see below for fleshed out example). These can be used without investments in advance planning.

Meso-metacognition – Use of tactics to promote metacognitive instruction throughout an individual lesson or when incorporating a specific type of activity (e.g. discussion or small group work) across multiple lessons. These tactics have been given more forethought with respect to integration with lesson / activity objectives.

Macro-metacognition – Use of more regular tactics to promote metacognitive instruction across an entire course / semester. Planning for these would be more long-term and closely integrated with learning objectives for the course or with professional development goals of the instructor. (For an example of this level of effort, see Use of a Guided Journal to Support Development of Metacognitive Instructors.)

Mega-metacognition – Use of tactics to promote metacognitive instruction across an instructor’s entire set of courses and professional activities (and beyond). At this level of engagement, metacognition will likely be a “way of doing things” for the instructor, but each new engagement will still require conscious effort and planning to support goals and objectives.

An Example of Micro Metacognition

Micro-metacognition efforts are not pre-planned when the instructional task is planned; they are added later as the idea crosses the instructor’s mind and opportunity arises.

For example, when I am about to start grading a specific group of papers, I might reflect that in addition to the formally-stated learning objectives that will be assessed on the rubric, I want to support growth mindset in my students for their future writing efforts. This additional goal could come about from a recent reading on mindset or discussion with my colleagues. I know that I would be likely to forget this goal when I’m focused on the other rubric aspects of the grading. So, I write that goal on a stickie note and put it where I am likely to see it when grading. Then, when I am grading, I have an easy-to-implement awareness aide to add comments in the papers that might specifically support my students’ growth mindset.

In sum: easily implemented stickie note –> promotes awareness of goal –> self-regulation of desired grading behavior on that specific instructional task == Micro-metacognitive Instruction!

I can think of lots of other ways instructors might incorporate micro-metacognition in their instructional endeavors, from the proverbial string tied to one’s finger, to pop-up calendar prompts, to asking a student for a reminder to attend to questions when we get to a particular topic. Or, awareness might come without an intentional prompt. The key is to then use that awareness to self-regulate some aspect of our instructional behavior in support of student learning and development. The opportunities are endless!

I hope you are motivated as you enter the new year. Happy holidays!

——————-

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning.

Poole, G., & Simmons, N. (2013). The contributions of the scholarship of teaching and learning to quality enhancement in Canada. In G. Gordon, & R. Land (Eds.). Quality enhancement in higher education: International perspectives (pp. 118-128). London: Routledge.

* Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U. S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Govt.

Personal Characteristics Necessary for Metacognition

By Lauren Scharff, Ph.D., U. S. Air Force Academy *

At my institution we have created the Science of Learning Team, a group of students who learn about the science of learning (including metacognition) and then lead seminars for other students who are hoping to improve their academic success. Additionally, as part of an ongoing scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) project, a small group of us (faculty and students) has assessed the efficacy of our various efforts to disseminate the science of learning to both faculty and students.

This past academic year I had the pleasure of working with Troy Mather, a senior who joined both the Science of Learning Team and the SoTL project effort as his capstone project. Below are some of his final reflections regarding his experiences helping develop his peers’ metacognition and learning skills. I believe they provide some great insights regarding the personal characteristics necessary for metacognition. He also shares some personal applications that many of us might use as a model as we work to develop metacognition in our students.

What is metacognition and why is it important?

My personal definition for metacognition is having the awareness to self- regulate your learning approaches through modifications or corrections. Having the awareness to identify what you need to work on or change gives you the opportunity to grow. It does require modesty and humbleness to look at yourself and be motivated to change something you see as an area for growth. If you are someone like me, who isn’t someone naturally gifted with academics, metacognition is a tool that you can use to guide your growth as a student and learner.

What is the biggest challenge to developing student metacognition skills?

The biggest challenge I see with developing student metacognition skills is the fact that this skill is largely correlated with maturity. Time is a limiting factor because developing self-regulation doesn’t happen overnight. This makes teaching metacognition hard because you can tell others the definition of the concept and why it is important, but you can’t make them internalize the importance or change their behaviors. However, I have seen that most students eventually figure it out with time and maturity.

How can we overcome this challenge?

Something I found to help students get on that track of appreciating metacognition is by providing some personal examples of ways I have self-regulated my learning approaches and made clear improvements. Students listen to those moments of success and often feel more willing to make changes or even become more aware of what they should work on. Sometimes this goes outside of the academic environment. For example, one of the ways I have been most impacted by metacognition is with my training to be selected for Special Tactics/ Combat Rescue following my graduation.1

I told my students in our Science of Learning seminars that my training experience was a journey of self-reflection and deep accountability. Every day I had to have the self-awareness and honesty to identify my weak areas and do something about it. Some days I didn’t want to drown in the pool. Some days I didn’t want to run a marathon. And some days doing thousands of body weight exercises when I was already sore was a miserable thought. But, I pushed myself to do those things everyday because I knew if I didn’t, I wouldn’t reach my goal. I got a professional free- dive instructor and a track coach to help me with my training regimen. It was metacognition that allowed me to see areas to improve and reach out for resources.

With academics, students need to take advantage of all the resources they have in front of them. But, this requires self-accountability to make those identifications and be willing to put in that extra work. I told our students about my experience training for Special Operations because they hopefully saw someone with high ambitions and the willingness to put in the work. Every once in a while, learners need a motivational story to put them on track to accomplish their own goals. I have learned that metacognition is the start to achieving any level of greatness.

Using Troy’s Examples

Troy mentions humbleness and self-honesty as underlying characteristics of successful engagement in metacognition. That is not an aspect of metacognition that I have seen widely discussed, but it’s a great insight. It can be uncomfortable acknowledging aspects of our own efforts that have not been successful, and then examining them closely enough to come up with alternate strategies. This discomfort is especially strong if the alternate strategies appear to require more effort, and we’re not certain that they will lead us to success.

Many of our students face these uncomfortable moments on their path to become better learners. Perhaps we can help them through these uncomfortable barriers by more openly acknowledging the discomfort in facing one’s shortcomings, and letting students know that they are not alone in experiencing discomfort. Motivational stories such as the one Troy shared can help ease the resistance to being metacognitive. I’m sure we can all come up with a personal story or two that illustrate our own experiences as developing learners in some realm. Hopefully we can move past our discomfort in sharing our struggles in order to motivate our students to face their own struggles and self-regulate to move beyond them.

————————–

1 Special Tactics/ Combat Rescue is an elite team within the Special Operations career field of the Air Force.

* Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U. S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Govt.

Metacognition, the Representativeness Heuristic, and the Elusive Transfer of Learning

by Dr. Lauren Scharff, U. S. Air Force Academy*

When we instructors think about student learning, we often default to immediate learning in our courses. However, when we take a moment to reflect on our big picture learning goals, we typically realize that we want much more than that. We want our students to engage in transfer of learning, and our hopes can be grand indeed…

- We want our students to show long-term retention of our material so that they can use it in later courses, sometimes even beyond those in our disciplines.

- We want our students to use what they’ve learned in our course as they go through life, helping them both in their profession and in their personal lives.

These grander learning goals often involve learning of ways of thinking that we endeavor to develop, such as critical thinking and information literacy. And, for those of us who believe in the broad value of metacognition, we want our students to develop metacognition skills. But, as some of us have argued elsewhere (Scharff, Draeger, Verpoorten, Devlin, Dvorak, Lodge & Smith 2017), metacognition might be key for the transfer of learning and not just a skill we want our students to learn and then use in our course.

Metacognition involves engaging in intentional awareness of a process and using that awareness to guide subsequent behavioral choices (self-regulation). In our 2017 paper, we argued that students don’t engage in transfer of learning because they aren’t aware of the similarities of context or process that would indicate that some sort of learning transfer would be useful or appropriate. What we didn’t explore in that paper is why that first step might be so difficult.

If we look to research in cognitive psychology, we can find a possible answer to that question – the representativeness heuristic. Heuristics are mental short-cuts based on assumptions built from prior experience. There are several different heuristics (e.g. representativeness heuristic, availability heuristic, anchoring heuristic). They allow us to more quickly and efficiently respond to the world around us. Most of the time they serve us well, but sometimes they don’t.

The representativeness heuristic occurs when we attend to obvious characteristics of some type of group (objects, people, contexts) and then use those characteristics to categorize new instances as part of that group. If obvious characteristics aren’t shared, then the new instances are categorized separately.

For example, if a child is out in the countryside for the first time, she might see a four-legged animal in the field. She might be familiar with dogs from her home. When she sees the four-legged creature in the field, so might immediately characterize the new creature as a dog based on that characteristic. Her parents will correct her, and say, “No. Those are cows. They say moo moo. They live in fields.” The young girl next sees a horse in a field. She might proudly say, “Look another cow!” Her patient parents will now have to add characteristics that will help her differentiate between cows and horses, and so on. At some level, however, the young girl must also learn meta-characteristics that make all these animals connected as mammals: warm-blooded, furred, live-born, etc. Some of these characteristics may be less obvious from a glance across a field.

Now – how might this natural, human way-of-thinking impact transfer of learning in academics?